[The Atlanta

Journal-Constitution: 12.02.2001]

A lost

boy discovers America

New life in Atlanta means mastering a

vacuum cleaner, keyboard, MARTA and the art of the job

interview

|

T. Levette

Bagwell/AJC

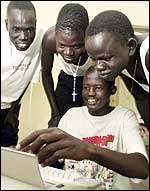

Roommates Peter Ayuen Anyang, Daniel

Khon Khoch and Marko Aguer Ayii (from left) look over

his shoulder as Jacob Ngor Magot tries out a

typewriter at their Clarkston apartment.

| By MARK BIXLER

Atlanta

Journal-Constitution Staff Writer

On his first

full day in the modern world, the young man explored a

kitchen. He opened a freezer, squinted at a package of frozen

beef and reached his hand in to feel the cold.

Then Jacob Ngor Magot, a thin man with impeccable manners

and an infectious laugh, turned to stare quizzically at the

white box with black coils on top. The cooking machine. He

turned a knob and held his right hand above one coil. Jacob

felt heat and yanked away his hand, eyes widening, a smile

spreading across his face.

It was a Thursday afternoon in a two-bedroom apartment in

Clarkston, 11 miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, and Jacob

was a bewildered time traveler in a strange new world. He was

four days and an ocean removed from a life of violence and

death in a land without electricity, telephones or running

water.

Jacob knew almost nothing of America, but he was in a hurry

to get his bearings and find a job. The U.S. government would

pay his rent and utilities and give him $200 a month for four

months.

Then he would be on his own.

Refugees begin this journey toward self-reliance the minute

they land in this country, but Jacob faced a more difficult

struggle than most.

His exodus began at age 5, when soldiers attacked his

village in southern Sudan. Jacob escaped but never saw his

parents again. He does not know if they survived. He marched

into the wild and eventually joined an estimated 17,000

children, mostly boys from a tribe called the Dinka. The

children wandered together for years. Nearly half were killed

by bandits and lions, starvation, disease or thirst.

"I walked all the way without somebody who was really

taking care of me," Jacob said. "I was not thinking I would

escape that situation, but God made it possible."

Jacob talks about his childhood with a quiet detachment. He

recalls matter-of-factly the boy who would have been killed by

a lion were it not for "the elder person who was having a

spear."

"One eye from that boy was removed," Jacob said.

He spent his teenage years in a refugee camp in Kenya,

sleeping in a hut with walls of mud and a roof of coconut

leaves and plastic. Aid workers estimated his age and assigned

him a "birthday" of Jan. 1, 1982. That would make him 19, but

no one knows his age for sure.

British missionaries taught him to add and subtract and

speak a stilted, formal English, but he lived without the

basics most Americans take for granted. He cooked over an open

flame, ate beans or maize and brushed his teeth with a

stick.

Coming to grips with Atlanta

|

1. An attack forces Jacob Ngo

Magot, 5, to leave his village near Bor, Sudan, in 1987.

He and hundreds of boys wander through the desert. He

eats leaves and wild fruit, but animals and disease kill

many friends.

2. Jacob arrives at a refugee

camp in Ethiopia after weeks in the wild. He lives there

four years. Hundreds of children like him starve to

death or die of disease. A new government makes the

children leave in 1991.

3. Soldiers chase

Jacob and other Lost Boys from the refugee camp. They

shoot and kill many and pursue others to the Gilo River.

Hundreds of boys, desperate, jump in. Crocodiles eat

several. Others drown. Jacob floats across on a car

tire. He is 9.

4. Jacob and other boys trek

through the desert to Pochala, Sudan, but unknown people

attack one night. They kill several children. Jacob is

exhausted but walks into the desert again.

5.

Animals and disease kill more children as they march

through the wild for months. Jacob arrives in August

1992 at a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya. He studies

English and math, attends church and eats grain once a

day for the next nine years. In July, at age 19, an

airplane takes Jacob from the camp on the first leg of a

72-hour journey to Atlanta.

|

Last year, he heard that the United States would give a

permanent home to him and 3,800 refugees like him. Authorities

resettled them only after concluding that their parents were

probably dead and that protracted war made southern Sudan too

dangerous for their return.

Aid workers called them the Lost Boys of Sudan after the

"Peter Pan" characters who band together to avoid the adult

world.

Jacob would go to a place called Atlanta.

He had never held a job or paid a bill, but Jacob was

desperate to support himself in Atlanta, to prove he could

survive once again. But what if no one would hire him? What if

Americans mocked him for knowing so little?

He thought about it on his first night in this country,

July 17, in a darkened hotel room in New York.

"There is a reason for me to be in the United States," he

thought, "but I do not know it, so I must ask God."

Jacob, a Christian, sat up in bed and prayed. He reached

for a small blue diary.

"What have you plan for me?" he wrote. "What are going to

be my achievements here in US?"

An airplane flew him the next day to Hartsfield

International Airport. A caseworker named Matthew Kon, also a

Sudanese refugee, ferried Jacob and three roommates in a Chevy

Blazer up I-85 and I-285. Kon's wards peered through windows

to absorb sights they had never seen before, so many green

trees and tall buildings and the river of cars flowing

alongside them.

That first afternoon, after exploring the kitchen, Jacob

retreated to a bedroom and envisioned his future by recalling

the past, by remembering what aid workers had told him about

America.

"We were told there is something here called entry-level

jobs, like cleaning, carrying things in a factory," Jacob

said. "You are the one to determine your need. If you fail,

you will not blame anyone."

To Jacob's left sat Peter Ayuen Anyang, the tallest of his

roommates, with high, pronounced cheekbones and the innocent

smile of a child. Beside Peter was Daniel Khon Khoch, wearing

the blue plastic rosary he has worn each day since an Italian

priest named Father Joseph gave it to him in 1994 for singing

in the refugee camp choir. Off to the side was Marko Aguer

Ayii, who struggled with English but laughed as freely as the

others.

Jacob sat on his bed, roommates quiet beside him.

"Most of us will be having no vehicles," he said. "It will

be difficult if you get a job far from your living

quarters."

The cars and trucks in Atlanta intimidated him.

"If you walk randomly, maybe a vehicle will knock you."

He also was intimidated at the prospect of dating American

women.

"We were told that, here, if you want to make friends with

a girl, she might have had a boyfriend and that boyfriend

might go and kill you," he said. "If a girl asks to make a

friendship and you say no, will she kill you?"

Jacob and his roommates passed those first days in donated

clothes furnished by the International Rescue Committee, the

resettlement agency that sponsored them. They wore T-shirts

that said "Married With Children" and "Imagination Station."

Belts looped twice around their waists.

Food was the most immediate problem.

"We are hungry but do not know what to make of the food in

our kitchen," Jacob said.

How to open cans with names like "Chef Boyardee Cannelloni"

and "Healthy Choice Chicken and Rice Soup"? What to do with

the bag of sugar? What about the mysterious container of

orange powder that Peter held aloft?

"It is written here 'Tang,' " Peter said, "but we do not

know if it is healthy."

They ate once a day, at night, as they had done for eight

years in the refugee camp, gravitating toward foods that were

not so exotic. They relied mainly on white rice and wheat

bread, but it was not just food that confounded them.

'We have to make eye contact'

Jacob had spent his whole life on flat plains with few

trees, a tabletop landscape where you see the sun the minute

it breaks the horizon. But there were so many trees in

Georgia. Jacob could see light for hours before he ever saw

the sun.

| SUDAN'S CIVIL WAR

|

.gif) |

A brutal civil

war in Sudan pits the Arabic and Islamic northern

government against the Christian and animist south. It

has killed more than 2 million people since 1983,

including hundreds of thousands of civilians. That's

more than the combined death toll in Afghanistan,

Bosnia, Chechnya, Indonesia, Kosovo, Sierra Leona and

Somalia. The war has produced an unusual group of

refugees called the Lost Boys of Sudan. Most were forced

from home after northern soldiers attacked their

southern villages in 1986 or '87. Many survived because

they were tending cattle in fields away from home, a

tradition in their Dinka culture. Most girls, older

males and adults were killed. The children formed a

river of orphans wandering together for years. Many were

killed by wild animals, bandits, disease or starvation.

Survivors wound up in a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya.

The U.S. government agreed to resettle about 3,800 Lost

Boys after authorities concluded that their parents were

almost certainly dead and that persistent violence in

southern Sudan made their homes too dangerous for their

return. About 170 Lost Boys live in metro Atlanta. Like

all refugees, they have legal permission to live and

work in the United States and are eligible for

citizenship after five years. A brutal civil

war in Sudan pits the Arabic and Islamic northern

government against the Christian and animist south. It

has killed more than 2 million people since 1983,

including hundreds of thousands of civilians. That's

more than the combined death toll in Afghanistan,

Bosnia, Chechnya, Indonesia, Kosovo, Sierra Leona and

Somalia. The war has produced an unusual group of

refugees called the Lost Boys of Sudan. Most were forced

from home after northern soldiers attacked their

southern villages in 1986 or '87. Many survived because

they were tending cattle in fields away from home, a

tradition in their Dinka culture. Most girls, older

males and adults were killed. The children formed a

river of orphans wandering together for years. Many were

killed by wild animals, bandits, disease or starvation.

Survivors wound up in a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya.

The U.S. government agreed to resettle about 3,800 Lost

Boys after authorities concluded that their parents were

almost certainly dead and that persistent violence in

southern Sudan made their homes too dangerous for their

return. About 170 Lost Boys live in metro Atlanta. Like

all refugees, they have legal permission to live and

work in the United States and are eligible for

citizenship after five years.

|

.gif) |

On his seventh day in America, Jacob and his roommates

walked behind Kon to the Kensington MARTA station for a lesson

on bus and train routes, important because Jacob would take

public transportation to whatever job awaited. He sat next to

Peter as they whizzed through a dark tunnel on the first train

ride of their lives.

"It is very, very, very, very long and very fast," Peter

said, beaming.

On the ride home, Jacob gazed through the window until he

saw the Kensington sign.

"We are supposed to alight here," he told the others.

A week later, Jacob rode MARTA to the IRC for a class on

job skills. He walked into a room where a yellow note on one

wall says "Wall" and another on a window says "Window." Robin

Harp, an employment specialist, talked about money.

"In the United States, there is an attitude that if you're

healthy and you're capable and you can work, then the

government should not give you money and you should work,"

Harp said.

She tried to brace them.

"Your first job will be difficult and you probably will not

like it, but remember, it's just a starting point," Harp said.

"You may have to ride the bus up to an hour and a half to the

job and an hour and a half back."

Back at the apartment, Jacob shared what he learned with

his roommates, who now included a fifth Lost Boy named John

Mach Rual. Peter had divined some of the same tips by reading

"Body Language in the Workplace," a paperback on their living

room coffee table.

"According to what I have read here, we can shake hands

with the interviewer," Peter explained. "We have to make eye

contact."

Jacob longed for an interview.

He waited.

The wonders of modern America

On Aug. 3, Jacob's 17th day in the United States, a

whirlwind of a woman named Dee Clement knocked on the door.

She is a volunteer who races in and out of the lives of many

of the 170 Lost Boys in metro Atlanta, delivering shoes and

towels and free life lessons. She strode into Jacob's

apartment with a typewriter, a Panasonic Jet Flow vacuum

cleaner and her dalmation, Polka Dot.

Jacob and his roommates settled into chairs in the living

room.

"This machine is a very, very special machine," Clement

began. "It's called a vacuum cleaner."

She picked hair from Polka Dot -- he was shedding -- and

sprinkled it on the carpet. Then she flicked a switch and the

very special machine started making noise. Jacob's eyes

followed the vacuum cleaner back and forth, back and

forth.

The dog hair was disappearing!

Clement taught them to peck keys on a typewriter.

"We all of us speak English Arabic Kishwahli and mother

tongueeee," Daniel typed. "America is the land of freedom.

America is multicultural land." And then, as Jacob talked

about bullets and fire that chased him from home: "Arabic

soldiers came and shot our people."

Soon Jacob fell into a routine. He went to church on

Sundays and attended GED preparation class from 5:30 p.m. to

8:30 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays.

"The problem that will lead me not to get a better job is

because I have no skill, and it is through college that I will

get that skill," he said.

He practiced tuning radios and setting clocks.

"I have learned to use telephonic communications," he

announced.

About this time, the IRC matched Jacob and his roommates

with a permanent volunteer, Cheryl Grover , a real estate

consultant for Verizon Wireless. Jacob rode to her house one

Saturday in August, awed on the way by the web of interlacing

concrete bridges people call Spaghetti Junction. He wrote

"Spageti Juncho" in his diary.

"This one is very, very technical," he noted. "Some cars

are moving up and others are moving down."

He was in Grover's living room 20 minutes later. One of his

roommates balled up in fright when Grover's dogs, Max and

Baby, bounded into the room. She led the dogs away and

returned to tell her visitors to have no fear because the dogs

were in a bedroom.

"The dogs have their own bedroom?" Jacob asked.

"No, no," Grover said. "They're in my bedroom."

In the kitchen, she showed them the whirring box of metal

and glass that cooks food with invisible microwaves. She

taught them to cook hot dogs, refried beans and oatmeal. Then

Grover led them down carpeted stairs to show them

computers.

"Dear Cheryl," John wrote on the computer. "I am John from

the land of Cush [Sudan] eager to learn a lot of things. I

have left my mum and dad in Africa due to the emerge war in my

territory. This war caused great separation of relatives in

Sudan and many destruction."

On a payroll at last

As August merged into September, Jacob began to worry about

money. The IRC had given him $400 in spending money in his

first two months, but he sent every dime to the refugee camp

in Kenya. He wanted to help a brother and two sisters who

stumbled into the refugee camp in 1998. Soon, though, he

realized he needed money in Georgia. He ran out of donated

MARTA tokens and spent money from his third check to buy

some.

Jacob did not yet know it, but he would be eligible to

apply for emergency IRC aid if he lacked a job after four

months. Caseworkers had not told him to encourage

self-sufficiency, but Jacob needed no prodding. Failing to

find work in four months would be a crushing blow to his

pride.

"Here in America, it is through jobs that you can make your

life to be very successful, but if you have no jobs, you

cannot make it," he said. "I cannot tell you that I will

really make it, but I am trying if possible."

Jacob finally had an interview Sept. 7, at the Discovery

Channel Store in Lenox Mall. He and John went with their IRC

job developer, Benjamin Cushman, whom Jacob reverentially

calls "Mr. Benjamin." Job developer Valerie Hardin brought two

other Lost Boys.

Jacob wore tasseled black loafers, khaki pants, a dull blue

shirt, neatly pressed, and a Navy tie with red polka dots.

"You look very nice," Hardin told him. "I don't think I've

had another client wear a tie for a job interview."

Inside the mall, Jacob craned his neck to survey the second

level. "It will be confusing if one is to get a job here," he

said. "If I come alone, how will I find the way I am to go to

my workplace?"

John marveled at the mannequins, human forms the color of

peaches and milk chocolate, lavished in furs and jewelry.

"Somebody who is not a millionaire cannot come and buy

something here," he said.

Jacob strode out of the interview with a poker face but

beamed as he got near John.

"I told him I am hardworking, punctual, willing to work,"

he said.

He went home confident, but the phone did not ring.

"We are worried," Jacob said later. "It is getting now a

long time without a job."

He could only watch Sept. 19 as two roommates, Daniel and

Marko, started work at an Emory University cafeteria. He had

applied at the Discovery Channel Store, Home Depot, Publix,

Target and the Westin Peachtree Plaza. As he waited, Jacob

watched television on a tiny set, read about the U.S. Civil

War and thumbed through driver's license manuals.

He talked about buying a car one day and moving to Gwinnett

County, where he had seen so much open space on rides to

Grover's house in Duluth. It reminded him of the wide, flat

savanna of southern Sudan.

Finally, a few weeks before Thanksgiving, the phone started

ringing with job offers.

Peter found work stocking shelves at Target. John and

William bag groceries at Kroger.

Jacob's job came days before his last $200 check.

He earns $7.25 an hour at the Discovery Channel Store and

$8.50 an hour stocking shelves at Target on North Druid Hills

Road.

Sometimes he works all night at Target, sleeps on the bus

and stocks shelves in the morning and afternoon at the

Discovery Channel Store. Recently he opened his first bank

account and deposited $1,400. He is tired more often, pays

more attention to time.

Jacob is relieved to be working, but he can't get too

excited. The Discovery Channel Store job is only part time. It

could end after the holidays. And a week after Jacob started

at Target, the store announced it would close for remodeling

in January. Jacob might have to find a new job all over again

next month. But he notices that most Americans somehow seem to

manage.

If they can make it, he says, maybe he can, too.

Back

to top | ajc.com

home

|