|

16 October 2002 Democratic culture and extremist

Islam

Werner

Schiffauer

| Are Islam and democracy

incompatible? The evolution of a radical Turkish

Islamic group in Germany suggests that the pursuit

of ‘fundamentalist’ goals can itself create the

space for a rational appraisal of tradition. By

seeking truth in origin and scripture rather than

history, successive generations of Islamists may

be drawn – even despite themselves – towards a

more flexible commitment to a network society of

social individuals. This may not yet be democracy;

but it is reformation. |

|

When the Caliphate State led by Metin Kaplan, the

most radical group of political Islam in Turkey, was

banned on 5 December 2001, one of its supporters said on

camera: ‘If one is a Muslim, one is not a democrat. If

one is a democrat, one is not a Muslim.’

Democracy is here condemned by these believers in a

very literal sense. The supporters of the Caliphate

State regard democracy as the embodiment of the rule of

polytheism. This is equated with the rule of evil as

such. Thus, some members of the community went so far as

to see in democracy the deccal, the Antichrist

himself, who also appears in the final battle between

the good and evil of Islamic eschatology.

It might be thought that this is all that needs to be

said on the subject of democratic culture and extremist

Islam. I believe, however, that this subject is more

complex than such explicit statements imply. My argument

is this: the internal logic of the fundamentalist

gesture itself gives rise to developments which call it

into question and, under favourable circumstances, can

transcend it from within. In order to elaborate this

thesis I would like to examine the radical critique of

democracy in the Kaplan community and to clarify what

conceptions of individual and society it is based

on.

Discontent with democracy, and the Islamic

alternative

My interlocutors in the Kaplan community were imbued

with a vision of unity. ‘Once one has understood, that

ultimately everything is one, then one has understood

Islam.’ The idea of a single, all-encompassing

God is combined with the idea of a single

undivided community. It finds ritual expression in the

so-called five pillars of Islam: the confessional

formula (‘I testify, that there is no God but Allah, and

I testify, that Mohammed is God’s messenger’), the

ritual prayer at five fixed times of the day, the

requirement to be charitable, the requirement to fast,

and the pilgrimage to Mecca.

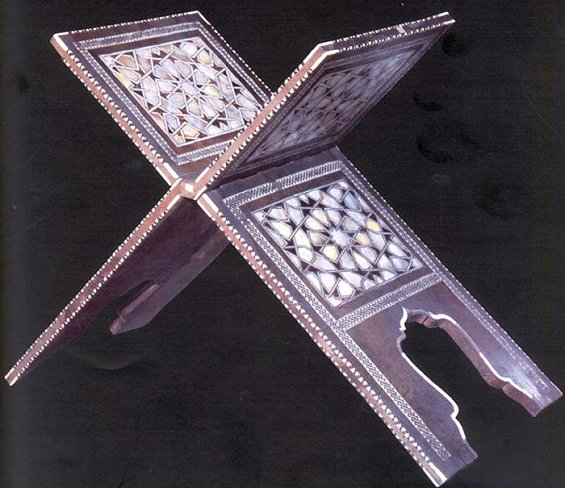

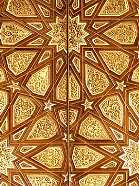

This unity is not an unstructured one. The ideal of

the inner structure can be exemplified by the star motif

of Islamic art. The illustration reproduced here shows

an inlay work on a 16th century Koran folding

lectern.

This star motif always seemed to me like a visual

rendering of a social and political vision. The societal

units interlock. Each unit – family, kinship group,

professional group, community, neighbourhood, enterprise

– is related to the whole, just like one of the larger

or smaller elements of the star motif to the pattern as

a whole. They form, as one would say today, a network.

The peace of society depends on the balance of the

elements.

Attention to boundaries plays a special role in the

preservation of the balance. Boundaries must never be

absolute, precisely because this would make the

interlocking and internal interpenetration impossible.

The ideal is not to supersede, to dissolve boundaries,

but to deal wisely with them. Dissolution is associated

with fitne – chaos, disorder.

In everyday life, this culture of the boundary is

expressed by a refined and elaborated ritualism; the

sphere of the other is observed and respected.

The idea of jihad is inscribed in this vision.

Jihad means ‘unceasing endeavour’ – and only one

meaning of jihad should be translated as ‘holy

war’. Ultimately jihad is directed at forces that

want to disturb the balance of the social order. At the

level of the individual, jihad means the battle

against the nefis (desire, egoism), which does

not accept the boundaries and calls them into question –

here, therefore, jihad means work on the self.

At the level of society it is the will to power, to

exploitation and expansion, which does not heed

boundaries and thereby calls the balance (and ultimately

the beautiful order) into question. In this case there

is a requirement of active resistance – if need be the

Muslim is called upon to take up arms. The Christian

idea of a principled profession of non-violence was

always very alien to my interlocutors, though the use of

force was only legitimate as defence. The resistance

both to the nefis and to usurpation appeared to

them to be prescribed by reason. They emphasised the

earthly responsibility for the maintenance of the

beautiful and rational order.

This Islamic vision of a network society forms the

background to their critique of parliamentary democracy.

The core of their arguments is that parliamentary

democracy is based on a culture of conflict; the

formation of opinion takes place in corporately

constituted groups, the parties, which form opinion

internally and then enter into debate with one another.

They are exclusive, to a certain extent autonomous and

can exist independently. They constitute distinct

identities. In such bodies the relationship of inside

and outside is fundamentally different from that in the

Islamic vision of the network.

Thus, the democratic culture of conflict implies the

sceptical idea of duality, as against the optimistic

idea of unity. Since no one owns the truth, regulated

forms of dispute must be established. Islamicist

dissatisfaction with this model is based on its

predisposition to discord, strife, and sham conflicts.

Against this, they evoke the dream of a scholars’

republic. Conflicts that arose were to be solved by

reference to the Koran, by obtaining a legal report, a

fatwa. The weight of such a report is

substantially dependent on the personal authority of the

issuer. Thus, unlike a court judgment, the legal opinion

given is only binding on someone who acknowledges this

authority. But personal authority develops out of the

free play of forces. What political Muslims have in

mind, therefore, is a scholars’ republic or a legal

opinion state.

The tension between theory and practice

How to implement this rigorous vision? If we now look

at the actual situation in the miniature universe of the

Islamicist communities in Germany, a noteworthy contrast

between doctrine and reality is immediately apparent.

From the start, several communities disputed the way in

which the social and political vision of Islam might be

advanced. It was interesting that there was no open

discussion and no openly conducted dispute about these

differences; but below the surface no holds were barred.

The early years, especially, of the establishment of

Islam in Germany, that is, from about 1968–1985, were

characterised by splits within mosques and by hostile

takeovers of mosque associations by competing

organisations. In other words, there were deep divisions

in German Islam. This was a problem, above all, for

Muslims themselves, who were very well aware of the

contrast between reality and beautiful ideal. They

tended to explain this in terms of human weakness and

inconsistency. I had the impression, however, that the

splitting was precisely a result of the consistency with

which they struggled to establish unity.

A small everyday observation encapsulates the

problems of the Islamic culture of conflict. In 1988, I

and my acquaintances from the Kaplan community called on

the Milli Görü community, from which the Kaplan

community had split off five years earlier. We were

courteously received as visitors. I was allowed to put

my questions, the hodja replied, my acquaintances

listened to him politely and agreed with everything with

a ‘tabii, tabii’ (‘of course, of course’).

To an outsider it would have presented a picture of

complete harmony; yet outside, the mood changed. The

hodja’s answers were torn to pieces. The whole

thing culminated in the sentence: ‘Did you hear, how

disrespectful he was of the other communities. That is

exactly why we left.’

I was told that there were questions I really should

have asked, in order to show up my opposite number. My

companions’ restraint inside the mosque reflects the

respect for boundaries. While in the other’s space, one

listens to him. To contradict him would violate the

rules of courtesy. Criticism may only be expressed when

one is outside again. The sociological problem of such

an ideal is obvious: an open argument is associated with

a rupture, with serious offence. ‘Divergence of opinion

[is] perceived as weakening the group and it [is] better

... to expel the oppositional group and let it go its

own way if it is too strong. Dissent is interpreted as

trauma, as a kind of terrible situation, because it

recalls the violence in Mecca before the triumph of the

one,’ writes Fatema Mernissi.

Islam within democracy: two routes

A historical sketch of two distinct communities of

Islam in Germany illustrates the argument I am making.

In 1984, Cemaleddin Kaplan broke with Milli Görü, the

European offshoot of what was then Necmettin Erbakan’s

Welfare Party. At the time, Milli Görü stood for the

parliamentary road to theocracy.

Cemaleddin Kaplan thought this route unrealistic,

especially given the experience of the state of

emergency in Turkey (1980–1983). If an Islamic party

grew strong enough to take power, the army would

inevitably intervene. Kaplan (whose doctrine developed

under the influence of the pioneering Islamicist

thinkers Al-Maududi and Sayyid Qutb) saw this dilemma as

revealing inconsistency in applying the ideal of unity.

The Islamic vision, he thought, cannot only be taken

seriously as a goal; the everyday political

struggle must also be guided by Islamic principles.

Thus, the party should be replaced by an open,

inclusive movement. The return to the original ideals

would allow the unfortunate split between the

communities to be overcome, leading to a stronger

position; the movement would take over the government in

Turkey and ultimately allow the Caliphate – the office

of the leader of all believers, which was abolished by

the Turkish revolution – to be restored.

Kaplan failed – even in his attempt to bring together

the believers (let alone his ultimate goal of taking

power). He wanted to overcome the division of Islam, but

instead did more to widen it than anyone else. This was

because his vision conflicted with the immanent logic of

the social. He failed to take account of the inertia of

established institutions. Contrary to his expectations,

masses of believers did not go over to him.

Kaplan was thus presented with a dilemma. A

charismatic, open movement must either take off – or it

disappears. Facing defeat, Kaplan tried to save his

programme, by turning the open, inclusive movement into

a sect and increasingly radicalising it. This included

the declaration of religious war on Turkey in 1992, the

proclamation of a separate state – the Caliphate State –

of which he declared himself Caliph. With each of these

steps, the borders with the other communities became

tighter and harder to surmount.

The history of the Kaplan community can be read as

exemplary of what happens to a group which attempts to

translate the idea of unity into action more

consistently and radically than everyone else – and

thereby merely deepens the divisions. This was also the

view of some within the community. Mehmet G., a

supporter from the very beginning, who was imbued with

the vision of unity, told me that he had fought for this

ideal all his life – and was now forced to conclude,

that he had only contributed to splitting the community

yet again.

The party that Kaplan left, Milli Görü, went in the

opposite direction. Its mother party, the Turkish

Welfare Party, underwent a remarkable development in the

1990s. It transformed itself from a party of notables,

the main strength of which was in rural Turkey – those

areas where the Kemalist revolution had only partly

prevailed – into a modern party whose main support was

in the gecekondus, the poor quarters of the

contemporary big city.

This expansion brought new groups into the party,

producing two distinct tendencies: a reform wing, whose

principal interest was in social policy (and which as a

result was willing to enter quite unprecedented

coalitions), and a wing which continued to emphasise the

cultural struggle against Kemalism. These two wings

co-existed, and debated their differences at party

conferences. As in the German Green party, a first

revolutionary (fundamentalist or ‘fundi’) generation was

followed by a second (realist or ‘realo’) fraction,

oriented towards Turkey and life in Europe respectively.

Yet in both Turkey and Europe, the integration of new

groups led to a process of pluralisation and the

emergence of new forms of dealing with conflict.

Conflicts were increasingly carried out by way of

discussions and ballots and thus did not immediately

lead to splits.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the

Refah (Welfare) Party, and its successor parties

today, had given rise to a democratic culture of

conflict. In terms of practical politics there is no

clear relationship between the social and political

ideals of democracy and those of Islam. Necmettin

Erbakan, for example, stands accused of saying different

things to different audiences. This can be seen, not

simply as political cunning or hypocrisy, but as the

everyday attempt to reconcile an emerging ‘culture of

conflict’ and an ‘Islamic network culture’. On the

whole, the opening to a democratic culture of conflict

was marked by success, whereas the radical adherence to

the vision of unity led only to further splits and hence

greater weakness.

The self and the individual

These political experiences have also found a

theological expression, in the discussion of whether the

society willed by God is best preserved by renouncing

the ideal of its complete earthly implementation, or

preserving the ideal as a standard of judgement about

the fallen world.

The Islamic vision of the network society also has

consequences for theological argument about the nature

of the self in the Islamic order. Islam emphasises the

divinity (and thereby the social nature) of man.

Nefis is the principle of desire and egotism, but

also of autonomy, which causes him to forget his

divinity and social nature. In Islam, the idea of true

self-discovery can be understood in terms of

self-surrender.

This idea can be spelt out in mystical terms or in

terms of ethical rules. The mystical idea is more easily

accessible, because it connects to widely familiar

experiences. In the act of love, always the model for

the mystical finding of self, one experiences oneself

most intensely (and only then) in forgetting oneself, by

disappearing into or merging with the other.

Surrendering oneself does not, therefore, mean denial of

fullness of being – on the contrary.

Mysticism transfers this humanly transitory

experience to the absolute Other – namely God, to whom

access comes via one’s spiritual leader, the sheikh. The

unimaginable intensity of the self’s merger with God,

like the moth which flares up in the candle flame and is

extinguished, is expressed by Celaleddin Rumi: ‘For

where love awakes, dies the self the grim despot / Let

him die in the night and breathe free in the rosy dawn.’

But the idea of finding the self can also be

expressed in terms of ethical rules. Here it is assumed

that the true experiences of self arise only through

inscribing the law in oneself. Whereas in mysticism the

dialogic concept of ‘I and thou’ is central (and God is

experienced by way of the ‘thou’), in the ethical

variant the ‘I’ experiences itself by merging with the

‘we’ of the community. In everyday life, a ritualism of

little steps represents one technique for embodying the

law; another form of its incorporation is learning the

Koran by heart. In these practices the word becomes

flesh and the flesh becomes word. There is a beautiful

translation of this idea in so-called pictorial

calligraphy, in which a body is formed out of the holy

script.

The follower of ethical rules finds the way to a

sense of self differently from the mystic, but the

fundamental idea is the same. In either case, it is

evident that this concept of the self radically

contradicts the ideas of individuality and autonomy, of

the existentialist view that each human being is under

an obligation only to his own law. The tension between

it and the idea of the individual on which a secular

democracy is based is also clear.

This conception of the self was especially apparent

in my conversations with older members of the Caliphate

State. They were imbued with it; but at the same time

there was a break. These men were migrants from rural

Anatolia, who in their childhood had been socialised

into the Islam of the village.

In this Islamic life/world, it is easy to acquire the

feeling that the social order, the biography of an

individual and Islam constitute an interlocking unity.

These men had no or only rudimentary schooling. When

they came to the city, they taught themselves reading

and writing, and were seized by a real hunger for

reading. Yet this reading consisted mainly of popular

religious texts: the stories of Mohammed and his

companions, books about the Caliphs who followed the

true path.

Their reading opened up a world to these men; it gave

them access to a special universe. This went hand in

hand with an overestimation of the written text. The

printed word seemed to them to have a particular

dignity, superior to that of the spoken word.

Gaining access to the truth in this autodidactic way

– as is clear from the history of the Spanish

anarchists, as from the Protestant fundamentalists in

John Wesley’s circle – often produces a combination of

overestimation of self and political radicalism. Among

these men, there was a very marked scepticism towards

the Islam taught in mosques in Turkey.

When they came to Germany, they found in Cemaleddin

Kaplan someone who formulated what they had always

thought, or rather felt, but had never been in a

position to express – the idea that democracy’s culture

of conflict is basically un-Islamic. It is evidence of

the remarkable self-confidence of these men of the first

generation, that they declared to me their readiness to

break with Kaplan, if they caught him departing from the

right way by even one iota; and not a few did precisely

that, when Kaplan proclaimed the Caliphate State.

A generational shift: from autodidacts to

intellectuals

The autodidacts revealed another tension, that

between the nature of their religious search and the

content of their thinking. They professed the core

belief in subordinating oneself absolutely to the law

and thereby transcending oneself. But they had arrived

at this substance by a very individual route: by way of

reading, of criticism, of choosing a teacher. In doing

so, they had already broken with a world in which the

validity of these ideas was taken for granted, and not

subject to analysis. They had thus consciously

appropriated and reflected a message, rather than had it

self-evidently communicated to them through ritual. This

break would grow larger with the next generation.

The children of these autodidacts passed through

German educational establishments. My book on the Kaplan

community tried to describe how they found their way –

often via a rebellious phase – to a radical form of

Islam. Significantly, they often began to take an

interest in the community at a point when their parents

were leaving it.

The difference between the two generations lies in

the relationship each establishes between unity and

truth. For the parental generation, the idea of unity

came first. When Kaplan proclaimed the Caliphate State

with himself as Caliph, they left him. They recognised

that he was thereby abandoning his original programme of

a revived unity of all Muslims; they rightly saw this

step as a way out of the ordained network. More than

this, someone who leaves the community is doing the

devil’s work.

In other words, the first generation sets the idea of

unity above that of truth. More precisely, it had a

procedural perception of truth. Mistakes are always

possible; there is always someone with a better

knowledge of the never-ending tradition, and that is why

it is important to remain in the community.

The next generation had gone to German schools and

universities and appropriated Islam differently; that

is, cognitively and with modern intellectual tools.

These were no longer autodidacts, but young

intellectuals approaching Islam within a wider

perspective. The essential was separated from the

inessential; known facts from ones that could simply be

looked up (although one had to know where). In other

words, a hierarchical, organised, internally-structured

knowledge took the place of an extensive, networked

knowledge. Such knowledge can easily give the younger

students in particular, the neophytes, the feeling of

possessing an Archimedean point from which the world can

be understood – and from which it can be turned upside

down. Most people who have attended Western educational

establishments will recognise this feeling.

Whereas the first generation came to the truth via

the idea of unity, the second generation came to unity

via the idea of truth. What ultimately would unity be

worth, if it is established on the basis of untruth? The

second generation saw themselves as truly Islamic

revolutionaries. Here we see, therefore, another

decisive break in the understanding of self; this

generation appropriated truth for itself, and demanded

that the rest of the community follow them.

In a way that may appear paradoxical, the second

generation is much closer to the non-Islamic social

majority than that of their parents. It is noteworthy,

and only superficially a contradiction, that its members

are much more dependent on authority than their parents.

They admired Kaplan not so much as someone who

articulated what they had always thought, but as someone

who offered them a perspective, from which complex and

contradictory knowledge suddenly assumed a shape.

It was inevitable that at some point, people would

turn against Kaplan by appealing to scripture. For

example, in 1987 a group of Islamic revolutionaries came

together under the leadership of one Hasan Hayr. When

Kaplan made a policy shift – he began to modify earlier

enthusiasm for the Iranian revolution – there was a

revolt by fervent Khomeini supporters. The form of the

dispute was especially interesting. The group had read

and discussed writings in favour of the revolution, and

on this basis wanted to force Kaplan to take part in a

discussion. He refused and banned them from reading

these, to him, dubious texts. The community split as a

result.

A third generation: the longing for origin

The logic of this story is clear: at some point a

third generation must arrive on the scene. The

beginnings are already in evidence, where an

individualised access to texts is taking place alongside

a growth in understanding of the relative nature of

interpretations and, therefore, of tolerance (the only

guarantee of avoiding isolation of believers). Among

sections of formerly Islamicist communities, there are

now declarations in favour of an Islam that demands an

independent treatment of the sources, thus establishing

a capacity for criticism. Voices of this kind are making

themselves heard everywhere in the Islamic world.

This is the paradox of every movement which has

dedicated itself to a return to the beginnings, which

seeks to restore the relationship of individual and

society as it was conceived and (possibly) lived in

classical Islam – for inside the desire to go back is

also a radically anti-traditionalist aspect. Tradition,

after all, can be understood as growth, as disfigurement

of the pure, the revealed, the true; it obstructs and

conceals the source. It has to be uncompromisingly

brushed aside, in order once more to gain access to the

original. With that, a specific dynamic involving both

individual and society is recast: society is now seen as

a project, and the individual as someone devoted to the

truth.

The defenders of tradition have always pointed to the

dangers inherent in this anti-traditional impulse. What

hubris, they claim, to dismiss centuries of exegesis and

scholarship in the name of individual access to the

tradition; and, consequently, what a danger of falling

prey to demagogues, who in the name of origins reject

the legitimate, socially anchored interpretation.

Yet in the rejection of tradition is the same impulse

that marked the origin of our modern democracy. The

individual adopts a new approach to tradition, and

derives from it a critique of society. Of necessity this

often has severe, even terrible, consequences. At the

same time – and this is what I wanted to show here – the

internal dynamic, the contradictions to which this

movement back to the source gives rise, contain an

awareness and an admission of relativity. This creates a

new contest for the truths that are now individually

acknowledged.

All this involves processes whose inevitable relapses

can, under certain circumstances, lead to barbarism and

catastrophe. I am nevertheless optimistic that something

new will emerge from this ferment.

My hope is based on the history of fundamentalism as

a whole. Islamic fundamentalism could develop in a

similar way to Protestant fundamentalism. Over the

generations it might lose its inflexible, rigorous

character, and only through this loss gain the power to

shape the world. Such a point is reached when a religion

articulates itself in earthly discourse as philosophy;

that is, when it articulates arguments without reference

to religion.

It may be recalled that Theodor Adorno (especially in

his later writings), Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer,

Jacques Derrida, to say nothing of Martin Buber and

Emmanuel Levinas are Jewish thinkers through and

through, and that their philosophies derive their force

from the secularised reformulation of originally

religious contents. Today, it is possible to imagine

that Islamic philosophers could use the strength of

Islam to elaborate a philosophy of the network society,

incorporating a wise treatment of boundaries and a

rethinking of the social nature of the individual.

Copyright © Werner

Schiffauer, 2002. Published by openDemocracy. Permission is granted to

reproduce articles for personal and educational use

only. Commercial copying, hiring and lending is

prohibited without permission. If this has been sent to

you by a friend and you like it, you are welcome to join

the openDemocracy network.

Werner Schiffauer

is Professor of Cultural and Social Anthropology at the

Europa Universität Viadrina in Frankfurt/Oder, Germany.

He has written and edited books on rural and urban

Turkey, on Turkish migrants in Germany (Türken in

Deutschland - Eine Ethnographie, 1991), on Islamism

in Germany (Die Gottesmänner - Islamisten in

Deutschland, forthcoming) and on foreigners in the

urban context (Fremde in der Stadt, 1997). He is

also a member of the Advisory Board of Ethos -

Journal of Anthropology and of the Council of

Migration Research.

|