|

The Satellite, the Prince, and Scheherazade : The Rise of

Women as Communicators in Digital Islam

By Fatema Mernissi

|

| copyright Ruth V. Ward

|

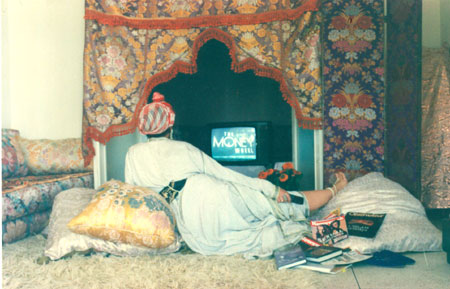

A professor

at Mohamed V University in Rabat (Morocco), Fatema Mernissi is

currently a full-time researcher at the IURS (Institut Universitaire

de Recherche Scientifique) where she splits her time between

animating writing workshops for civic actors seeking to influence

public opinion through publications and conducting her own

field-work based analysis of Moroccan society. When MBC, the first

satellite-TV, hit the Moroccan sky in 1991, she switched from the

study of the Harem (a world view where space is sexualized-the

private is confused with femininity and the public with

masculinity-which is the theme of her early publications such as

'Beyond the Veil,', 'The Veil and the Male Elite' and 'Forgotten

Queens of Islam'), to the study of the 'digital umma,' where she

focuses on the new sexual and political game produced by the new

communication technologies demolition of frontiers. Her latest book,

"Les Sindbads Marocains:Voyage dans le Maroc Civique"(Editions

Marsam, Rabat, March 2004), describes how the previously isolated

desert youth in the South of Morocco are transforming themselves

into skilled navigators on the internet in

cyber-cafés.

During Ramadan

2002, I realized that I was becoming a stranger in my own land and

that the old Arab world I was born in and could decode and

understand has vanished forever. Women managed to shock the digital

Umma (the new satellite-connected Muslim community) not only by

belly-dancing in the most popular television series, but also as

producers of films and as talk show anchors. "In spite of the great

variety of their topics, the Ramadan television series have one

thing in common, regardless of whether their subject is social,

historical or religious: the unavoidable belly-dancer who has become

a pivotal creature in the events unfolding in these shows," explains

Mohammad Mahmud, the columnist who reports on talk shows in the

prestigious weekly Al-Ahram Al-Arabi. What surprised him most was

her versatile dimension: "The belly-dancer is the key figure who

helps businessmen rise to the top or pulls them down to the abyss.

In one television drama, the belly-dancer plays the heroine of the

popular struggle for liberation, in another, she backs a Zionist

movement supporter.... Does this extraordinary presence of the

belly-dancer in the Ramadan television shows reflect reality or is

it simply a seductive maneuver on the part of the producers to

attract audiences?" (1) One has to sympathize with the Al-Ahram

columnist, because it is not belly-dancing he is complaining about

per se; as everyone knows, unlike some puritanical Christian

Scandinavians or Americans, Arab men in general, and Egyptians in

particular, are thrilled by such a sight. What he is worrying about

is that the ever present-belly dancer interferes seriously in the

spiritually-inclined believer's capacity to transcend the

voluptuousness of the senses and concentrate on more esoteric

blessings. To help man reach harmony (wasat), that, is to

develop a balanced set of defense mechanisms which allows him to

resist temptations without drifting into ascetic extremisms, is

after all the key ideal Islam has been promoting for the fifteen

centuries of its existence (the year 2002 corresponds to the year

1423 of the Muslim calendar). But Arab satellite-television somehow

seems to capture the intoxicating pre-Islamic spell of women and

fuels it with an alarming glow.

1. Women's

Aggressive Invasion of The New Public Space of the Satellite-Wired

Umma

After asking

the questions, Mohammad Mahmoud reminds everyone that Ramadan is

indeed a fantastic opportunity for film producers because during

that month hungry believers rush to their homes to break the fast

and are therefore easy prey for television programmers. He proceeds

to quote Taha Hussein, one of the twentieth century's most

remarkable Arab thinkers, to make his point clearer: "Is not Ramadan

the month of spirituality and the occasion to get nearer to Allah?

Should we not expect the television drama during this sacred month

to nurture our pious cravings?"

But the

belly-dancers were not the only aggressive women who managed to

invade the political space created by satellite television. One of

this Ramadan's highly polemical and most challenging, as well as

popular, television series was not the controversial "Rider without

a Horse" (Faris Bila Jawad), which was identified as

anti-Zionist and condemned by many American and Israeli media

organizations. Instead, it was a film by a female movie director,

In'am Mohammad Ali, about a highly controversial Egyptian male

feminist, who wrote "The Liberation of Women" (Tahrir

al-Mar'a), a vitriolic pamphlet on sexual equality which was

perceived as scandalous by Arab rulers in the 1930s. The man's name,

Qasim Amin, is also the title of the television series which

competed for stardom with "Rider without a Horse" on many of the

fifty or so Arab satellite channels during Ramadan. Both films are

set during the 1930s British occupation of Egypt and both take their

viewers into politically entangled romantic tales set in the harems

of the corrupt Turkish Sultan who then ruled. But while the hero of

"Rider without a Horse" mingled with the British upper class and

tried to profit from it in an opportunistic way, "Qasim Amin" forces

the viewer to reject that ruling class as inhuman, because he

identifies "with his humiliated mother and with one of her

co-spouses who were suffering from the arrogance of the harem

master." What made male viewers very attentive to Qasim Amin was

that its female movie-maker, one of Egypt's most talented

professionals, "showed, through her film, that when a competent

artist decides to take us to navigate in the past, it is not so much

to seek an escape from reality as to enlighten it".(2) The film's

key message was that in 1930s Egypt just as today, to liberate women

is the best chance to empower the country and release Arabs'

energies. While "Rider without a Horse" identified a Zionist plot,

that is, an external force, as the reason for Arab weaknesses, the

Qasim Amin serial focuses on the internal mechanisms of

powerlessness, on the psychological dimensions of Arab weakness, and

is, according to many media commentators, a much more corrosive

invitation to an exacting self-introspection.

However, the

aggressive invasion of Arab media by women as actresses and

producers of films and shows as well as directors of television

channels did not start with this Ramadan. "The Empire of Women" was

the scary magazine cover story which revealed to male Egyptian

citizens that "of the 80,000 persons working in the radio and

television, 50,000 are women." (3) The article went on to explain in

detail "how clever women were strategizing to obtain

(istiyad) top positions in management hierarchies as well as

radio and channel leaderships." 3/ The fact that women were visibly

present in Arab media was not really the breaking news. What rang

strange bells in that sacred month was that the extraordinary appeal

of the female hostesses of Al Jazeera was due to their breaking of

sexual taboos.

2. The Big

Satellite Scare: Al Jazeera Women Probe Sexual

Inadequacy.

This summer, I

became terribly jealous of Muntaha al-Rimhy, one of Al Jazeera's

most intellectually sharp anchor women: men were talking non-stop

about her all along the sandy Atlantic beaches around Casablanca I

visit regularly. The reason was the talk show she devoted to probing

"the reasons for the lack of sexual desire among spouses." And since

the talk show's name is "For Women Only," what scared the male

viewers was that only she and her three female guests were voicing

opinions on this troubling phenomenon which they described as

widespread and statistically alarming. "Muntaha al-Rimhi," comments

Ali Aziz, a male television columnist "decided to break a taboo on

her Al Jazeera show, by inviting her all-female guests to probe the

lack of sexual appetite (futur) between spouses. The three

guests went into detail with their hostess, diagnosing the problem

which is growing in prodigious proportions, according to them, and

identifying its superficial and deeper reasons. The women dived into

psychological explanations, unearthing the emotional as well as the

educational dimensions of the problem." The word chosen by the

show's hostess was a tricky one. She deliberately avoided talking

about sexual impotence ('ajz) and used the wicked

futur," which literally means "a loss of energy level, a

sudden weakness." This left male viewers wondering. As one of my

university colleagues remarked, "I wish Muntaha had chosen to speak

about straightforward sexual impotence, because when a woman speaks

about futur, the man immediately feels guilty and

inadequate." My Moroccan colleague was right, because what made the

Egyptian columnist feel uneasy was simply that women were talking

publicly about sexuality in the absence of an important actor-the

man. "Although the non-expert male viewer did not get enough

information from the show to make up his mind," explains Ali Aziz,"

it was nonetheless quite an impressive display of acute analysis and

perspicacity. You really need to see only three women sitting

together, even if silent, to make you realize the gravity of such an

impediment as the lack of sexual appetite." (4)

Yes, the new

information technology is definitely producing cataclysmic

psychological changes in Arab self-perception, but what is more

astonishing is that the invasion of women as aggressive participants

in the new satellite TV is only a mirror of what is happening

everywhere, in a less visible way, such as the more intimate surfing

on the net in the dark corners of the mushrooming

cyber-cafés.

3. "Is

Internet Chat Licit (Halal) During Ramadan?" Teenage Girls Ask Azhar

Sheikhs.

This Ramadan was definitely very different,

considering the request for a fatwa from Egyptian sheikhs on the

following issue: "Is chatting on the Internet forbidden during

Ramadan?"(5) Unlike what we think today, fatwa in early Islam had no

power connotation. Fatwa meant simply that "you ask a question" to

inform yourself, explains Ibn Manzur in his 13th century Lisan

al-Arab ("The Tongue of the Arabs"), which is still used

today.(6) If there is to be fear, it should be on the part of the

religious authority whose duty is to put its expertise at your

disposal to help you solve your problem. The fatwa is a test for the

authority, not for the questioner. Thus Egyptian youth's inquiry

about chat rooms supposes that the sheikhs at al-Azhar University

are digitally competent. Indeed, the internet is reviving the oral

tradition of Islam begun by the Prophet in Medina. Asking for a

fatwa was part of the constant interactive dialogue technically

known as jadal, which helped the prophet build a formidable Muslim

community in less than a decade (between 622 and 632). (7)

The

challenging Ramadan question about internet chat was accompanied by

a huge picture of two adolescent girls surfing on computers and a

discreet caption which makes us realize the gravity of the inquiry:

"Many youths are forced, because of their jobs, to surf the internet

... How is their fasting affected, for instance, if they happen to

encounter, by chance, a pornographic website?" (8) This is one of

the delicate questions which Jamal al-Kashki, editor of the Ramadan

issue of the widely circulated Egyptian magazine Al-Ahram Al-'Arabi,

identified as significant for al-Azhar sheikhs to answer, if they

wanted to stay credible in the eyes of the blushing teenagers. And

don't make the mistake of thinking that those who claim to speak in

the name of Islam are technologically backward and that they are

internet and satellite illiterates. Believe it or not, it is the

most conservative of all, the Iranian Ayatollah of the Center for

Islamic Jurisprudence of the city of Qum, one of Shi'a Islam's

capitals, who first rushed to the web with the strategic intention

of outdoing their fifteen-century-old Arab Sunni rivals. "Several

thousand texts, both Sunni and Shi'a, have been converted to

electronic form," explained one of the contributors to a 1999

retrospective on Digital Islam. "While Sunni institutions tended to

ignore Shi'a texts, the Shi'a centers are digitalizing large numbers

of Sunni texts in order to produce databases which appeal to the

Muslim mainstream, and hence capture a large share of the market for

digital Islam." (9) However, here, I want to focus on the impact on

one single dimension of the new information technologies which seems

to me particularly exciting, namely satellite broadcasting, because

it creates the highly political public space where the entire

community is gathered to debate vital issues. By contrast, the

internet, which is basically more of an individual experience, does

not have that theatrical public dimension, so central to Islam,

where the sexes are not supposed to have the same access and the

same behavior. Let's not forget that the Umma, the very concept of

the community in Islam, does not refer so much to a static entity as

to a dynamic communication-fueled group.

4. The

Umma-the Muslim Community-Refers to a Communication Synergy, Not to

a Static Entity

Let's not

forget that the Umma, the very concept of the community in Islam,

"means a group moving towards the same goal." (10) Constant

communication within the community is what enhances its dynamism,

which is why satellite broadcasting transforms the Muslim dream of a

debate-linked planetary community into a virtual reality. But by so

doing, satellite broadcasting challenges the behavioral code which

sets different rules not only for the sexes but also for religious

and political minorities. It is this challenge which explains both

why Muslims have become so intoxicated with the new technologies and

why focusing on the satellite's impact is the best angle from which

to decode the digital Islam puzzle. Yet, as enigmatic as the future

of this digital Islam might look to us today, one thing is certain:

most key players, from orthodox (Sunni) Saudi oil princes to Shi'a

Iranian ayatollahs, have grasped that power will belong to

satellite-equipped communication wizards. And this explains the

discreet but nevertheless ferocious race for digital power among

Muslim countries where even elementary notions such as

"center-periphery," which should give a geographical advantage to

the Middle East, are challenged. "A country such as Malaysia,

usually considered to be on the margins of Islam both in terms of

geography and religious influence, has invested heavily in

information and networking technologies." (11) The Iranian

ayatollahs rushed to invest in the new technologies in the early

1990s but Saudi oil princes were more cunning in that they realized

early on that they had a fantastic advantage over Iranians and

Indonesians. Since the Arabic language happens to be the sacred and

common medium, investing in satellite communication was the shortcut

to global supremacy. Saudi Arabian propagandists were the first to

create planetary media lobbies; in the l980s, they armed themselves

with digitally printed transnational newspapers and satellites.

5.

Advocates of Islam from Saudi Princes to Hezbollah are Armed with

Satellites

The two most

widely circulated Arab newspapers are the London-based and digitally

printed Al-Hayat ("Life") and Asharq al-Awsat ("The Middle East").

Both are controlled by Saudi princes: Al-Hayat by prince Khaled Ibn

Sultan, the son of the Saudi defense minister who led his country's

troops during the Gulf War, and Asharq al-Awsat, which has a staff

of 150, sells 80,000 printed copies, and is accessible to 100

million readers on the Internet; the latter belongs to another Saudi

prince, Salman Ibn Abdelaziz, the governor of Riyadh and the brother

of the King of Saudi Arabia. But you only get an idea of the scope

of the Saudi princes' investment in the new information technologies

if you remember that MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center), the

first satellite channel to hit Arab skies, in 1991, belongs to

"Walid al-Ibrahim, a brother-in-law of King Fahd Ibn Abdel Aziz

al-Saud" and that the next to follow two years later, ART (Arab

Radio and Television), is "owned jointly by the Saudi entrepreneur

Sheikh Saleh Kamel and Prince Al Walid bin Talal Ibn Abd Al-Aziz, a

nephew of King Fahd." (12) It is not therefore surprising to

discover that the Iranian Ayatollahs made the same calculation when

Iran backed Hezbollah and helped it launch the Arabic-speaking Al

Manar channel. This channel "belongs, via the Lebanese Information

Group headed by Nayef Krayyem, to Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed

Lebanese Shi'a Muslim group founded to resist the Israeli occupation

of Lebanon in 1982. Hezbollah started terrestrial broadcasting in

1991 and eventually gained official broadcasting licenses for the

al-Manar television channel and the al-Nur radio station."

(13)

I mention this

merely to caution the reader to avoid the stereotype which links

Islam with archaism. This is a fatal strategic mistake, not only

because the new technologies are being used as instruments by its

advocates, but also because the competition in the market for

digital media products is forcing the producers to shift to free

speech and interactive dialogue. Since the September 11 attack, all

media lobbies, be they Saudi or Iranian-owned, who used to scorn

Arab citizens and club them with one-sided propaganda, are now

shifting to interactive programming to please viewers who can surf

freely and zap between channels because satellite broadcasting has

destroyed state boundaries and empowered illiterates. Satellite

broadcasting "by passes the two most important communication

barriers-illiteracy and government control of content." stresses

Hussein Amin. This revolution is radically changing roles: citizens

have shifted from being manipulated pieces on the chessboard to

becoming its major players.

Zapping among

channels has become an Arab national sport. Empowered by cheap

satellite household dishes which allow them to surf between

fifty-plus Arab satellite channels, previously passive Arab viewers,

of whom half are women, have become ferocious "zappers" and choosy

audiences difficult to please. Consequently, you can no longer have

access to Arab oil by manipulating only Arab heads of state,

diplomats and army generals. The new information technology is

forcing all Middle East chessboard players, local and foreign,

including Americans, to create Arabic channels. The decision of both

Iran and the United States to launch Arab satellite channels to

communicate with the masses, illustrates this digital

technology-induced shift of power from the states' bureaucratic

elites and private oil lobbies to citizens. Hussein Amin has

predicted in his "Arab Women and Satellite Broadcasting" that this

new technology "has the potential to empower Arab women in the

exercise of their right to seek and receive information and ideas."

(14) His prophecy seems to be starting to materialize and change

reality.

6. The

Planetary Race to Create Arab Satellite Channels: Iran and the U.S.

Search for Skilled Male and Female Journalists

One of the

booming businesses in the Middle East region since the September11

attack has been the recruitment of intellectually powerful men and

women with adequate training in both writing and communication

skills. They are needed because Arab audiences have deserted

entertainment channels for the "24-hour news" channels, such as Al

Jazeera and more recently Al-Arabiya. One of the reasons which

explain the Saudi MBC's catastrophic loss of audience, and its

consequent financial troubles, was the fact that Arab audiences were

fed up with its mix of entertainment and religious propaganda and

deserted it as soon as Al Jazeera started its 100% news channel in

1996.

During the

Moroccan elections in the fall of 2002, the gripping headlines were

not about who lost seats in the parliament but the fact that Iranian

ayatollahs had sent their agents scouting our country looking for

the best of the local television journalists, offering them huge

salaries. "Iran is launching an all news satellite channel which

will be broadcasting in Arabic from Teheran ... Many of the Moroccan

journalists approached by its recruiters were hesitant at

first...but succumbed when Iranian investors offered salaries as

high as 3,000 dollars a month." (15) The other gripping event

heavily commented on in the entire Middle East press, was the

decision of the Bush administration to invest $500 million in Arab

satellite TV and the subsequent rumors of its "buying" brainy Arab

journalists from the prestigious London-based newspaper Al Hayat and

training them in TV broadcasting in the Beirut-based channel LBC

(Lebanese Broadcasting Center). (16)

7. The

Lebanese are Helping Americans to "Buy" Eloquent Arabs from Al-Hayat

to Staff their Washington Channel

One of the

most "shocking" rumors after September 11 was that of the sudden

merger between the Saudi-owned newspaper Al Hayat and LBC (Lebanese

Broadcasting Corporation), "which started as a Maronite militia

channel in the civil war," (17) according to some analysts and is

"controlled by a board dominated by ministers and officials close to

the Syrian government" (18) according to others. It was formed to

help Washington recruit competent communicators for its new Arabic

channel-hence the suspicions raised by this business deal, which is

considered by many a conspiracy that ought "to be evaluated in the

light of the latest media wars in the region ... starting with the

American decision to launch an Arab channel as part of its

post-September 11 communication strategy." (19) It is true that one

of America's main problems since the September attack is how to

communicate with Arabs. How to sell America to the Arabs has become

a strategic concern: "The Bush administration has been looking at

new ways of combating anti-Americanism." (20) David Chambers

explains in his article, "Will Hollywood Go to War?" that "a new

consideration starting in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee is

a bill called the '9/11 Initiative' to invest $500 million in a

pan-Arab satellite TV channel to combat the media influence of the

increasingly successful Al Jazeera and to target Muslim youth." (21)

But to communicate with Arabs, buying the hardware and access to

satellite platforms is not enough. It is rather more difficult to

find convincing communicators like Al Jazeera's who win audiences by

transforming talk shows into "boxing rings."

8. Ghada

Fakhri or How Scheherazade Got on the "Wanted" List

Iranians,

Americans and Saudi Emirs look for very specific types of

journalists to recruit: intellectuals who are trained in writing

techniques and also have television experience. Ghada Fakhri is such

a person: "Ghada Fakhri used to work with Asharq al-Awsat, then she

worked for Al Jazeera as a correspondent in New York, followed by

being a correspondent for Abu Dhabi Television before we succeeded

in tempting her to join our project." The man talking with so much

enthusiasm about the talents of Ghada Fakhri is Salamah Nemett, a

Jordanian with experience in both printed and visual media. LBC

recruited him as managing editor for the newly-created "SuperNews

Center" whose objective is "to train print journalists in TV

journalism." (22) However, the Lebanese are not admitting that they

are serving as middlemen for the Americans. If you asked LBC's

chairman, Sheikh Pierre Daher, what was the objective of his merging

with Al Hayat and locating the "Super News Center" in London, he

would answer that he was recruiting journalists like Ghada Fakhri

solely to improve his channel's own political coverage and its news

product. But "according to analysts ...there is a

Saudi-Lebanese-American concentration" (23) which is trying to lobby

in the United States to profit from market openings in this new

communication war.

In any case,

what I want to stress here is that the rising demand for articulate

intellectuals who combine writing and television experience in the

new communication wars in the Arab world is giving women a golden

opportunity to enter the power game in the Middle East. Although in

a country like Egypt which has a powerful movie industry (ranking

third after the US and India) women have managed to compete for

higher positions, their influence has remained local. With the

satellite media industry, Arab women are competing for pan-Arab

influence and, beyond it, for global sway. But to understand better

the empowerment dynamics of satellite broadcasting, one has to keep

in mind the intense competition not only among channels but also

among satellite operators which is forcing everyone to switch as

fast as possible from manufacturing propaganda to responding

attentively to the citizens' needs.

9. The

Explosion of Satellites Has Turned Arab Citizens-Women Included-into

Profitable Audiences.

The explosion

of satellite broadcasting has transformed the passive Umma everyone

was abusing into a precious audience for advertisers-an audience

including 36% illiterates, of which 64% are women. (24) The

proliferation of satellites launched in the Mediterranean region, by

both Arab and non-Arabs, has heightened the competition for

audiences among all sectors, public and private, legitimate and

terrorist: "Between 1998 and 2000, several satellites equipped for

digital compression were launched to serve areas that included Arab

states. Besides Egypt's Nilesat 101 and 102 and the new generation

of Arabsat craft, starting with Arabsat 3A, the HotBird satellites

of Europe's operator, Eutelsat, also transmit to viewers in the

Mediterranean Basin and parts of the Gulf." (25) This proliferation

of satellites has made it possible for smaller operators to compete

with the propaganda-manufacturing oil lobbies and it has reduced the

latter's revenues by fragmenting the audiences. Because of the oil

reserves, all major players-be they private investors, like Saudi

princes, heads of state, or ayatollahs-have to listen carefully to

what the viewers want, both to gain political power by influencing

public opinion and to attract advertising. "With a population of

over 300 million people, all speaking the same language in a highly

strategic region of the world," remarks Sheikh Pierre Daher, LBC's

chairman, "we have all the potential we need to compete with the

rest of the world, and attract billions of dollars in advertising

budgets. If we don't do it, someone else will." (26)

Women are

among the winners in this power shift because "the new information

technologies are basically anti-hierarchical and detrimental to

power concentration," explains Nabil Ali, an Arab linguistics and

digital technology expert. "Destroying space and time frontiers ...

these technologies blur the familiar distinctions our civilization

has operated on up to now, such as the separation between student

and teacher, learning and teaching, production and consumption...."

(27) It is precisely the collapse of this latter distinction which

is radically transforming the Arab World.

The irony is

that the camp of pluralism and democracy is rapidly winning in the

Arab World since September 11, not because the left has won the

battle, but because the conservative heads of state and oil princes

who have invested their assets in extremist propaganda, are now

shifting to courting audiences in general and promoting women in

particular. In her assessment of the "New Order of Information in

the Arab Broadcasting System," Tourya Guaaybess makes the ironic

comment that we are witnessing an unexpected "growing market of

political liberalism." (28) In any case, it is startling to realize

that the much longed-for democratic revolution is happening in the

Arab world not because the left has subverted the system but because

authoritarian regimes and oil-lobbies are rapidly realizing that in

a cyber-Islam galaxy, you can only remain in power if you share it

with citizens of both sexes.

10. MBC'S

Money-losing Singing Girls versus Al Jazeera's Female

Stars

According to

the latest news, MBC 's emergency move from London to Dubai was " to

get closer to its viewers so as to arrest its financial decline due

to a catastrophic shrinking of audiences." We want to be closer to

our audience," (29) said Ali Al-Hedeithy, MBC Director General, when

asked to justify his hurried move to Dubai and his decision to

launch a new MBC all-news channel like Al Jazeera. One of MBC's

problems is that Arab female audiences seem to stick with al-

Jazeera because of its rebellious images of femininity.

MBC was

extremely popular when it started in 1991. It used Arabsat to target

the Middle East and North Africa, Eutelsat to reach Europe's 20

millions viewers and ANA (The Arab Network Agency) to recruit an

American audience. MBC was then the only satellite channel, but soon

its "12.5% religious programs, 75.5% entertainment, and only 9.5%

information" (30) got on the Arab viewers' nerves. Consequently,

they deserted it in 1996 when Al Jazeera gave them the opportunity

to see uncensored news twenty-four hours a day. But the other reason

was that MBC's systematic censorship was projected through the

superficiality of its entertainment programs, alienating viewers,

especially women. "These channels' activities were reduced to a

frantic parade of male and female singers" explained Walid Najm, one

of the experts invited to diagnose the viewers' desertion. "One

could say that such channels programmed citizens to hope to achieve

one single objective: to become male or female singers." (31) Other

stations like it, who also violated citizens' right to information

and reduced talk shows with intellectuals to pitiful masquerades,

were deserted as soon as Al Jazeera offered a different image of

both informer and informed.

"MBC set out

originally to be the CNN of the Arab world," explains Ian Ritchie,

its former CEO. Once the channel started losing money, "my mandate

was to change it into a more commercial channel and therefore the

news played less importantly perhaps than entertainment and sport,

because that was what advertisers want to see. That's why I did the

deal to bring the US Champion League to MBC and a deal for "Who

Wants to be a Millionaire?" (32) Entertainment meant promoting

singing and dancing men and women and it proved to be fatal

business-wise, because Middle Eastern women were interested in al

Jazeera's more energetic femininity: "One of Al Jazeera's programs,

"Sports News" (Akhbar Riyadiyyah), has devoted several

episodes to the role of Arab women in sports and has highlighted the

championships that have been won by various female sports figures."

(33) Besides sports, it is the forceful female news anchors who

fascinate both men and women. A news channel such as Al Jazeera,

funded by the Emir of Qatar with the objective of strengthening

civil society and free speech, offered the possibility of becoming

stars to intelligent, articulate speakers and program hosts of both

sexes. Therefore, it is no wonder that MBC shifted assets from its

money-losing entertainment channel to launching a new channel

devoted to information only. To catch up with Al Jazeera, MBC

started looking for smart professional men and women rather than its

usual singers, but it has to compete for such talent with Iran and

the U.S.

11. The

Fascination of Arab Audiences with Strong Female Hosts and War

Correspondents

Promoting

strong female stars has proven to be a fantastic asset for the

Saudis' most threatening TV rival. Al Jazeera is winning crowds

every night through the eloquence of its news anchors Jumana Nammour

and Khaduja Bin Guna, and economics expert Farah al-Baraqawi. While

state-owned televisions and oil-funded channels traditionally

censored their staff and denied them the right to decide freely

about their programs' content and their guests, Al Jazeera's success

is due precisely to the freedom its programmers and speakers enjoy,

which allow them to become credible communicators. "Channels that

want to be viable are required to rely much more heavily on

high-impact 'brands' and product lines. Al Jazeera demonstrated the

value of such assets when it developed a range of programs whose

titles and presenters have become household names inside and outside

the Arab world," explains Naomi Sakr, the author of "Satellite

Realism: Transnational Television, Globalization and the Middle

East." (34) The most famous reporters in the Middle East today are

probably the Palestine-based Al Jazeera reporters Shirin Abu 'Aqla

and Jivara al-Badri, who are admired for their courage and

professionalism. "History will remember that day when there was no

one to speak up in the entire Arab nation, from the Atlantic to the

Persian Gulf, but women such as Shirin Abu 'Aqla and Jivara al Badri

and Leila Aouda," comments Ali Aziz, the columnist of the Egyptian

magazine Al-Nuqqad ("The Critics"), "while male leaders and

gallon-hat wearing generals have disappeared from our sight and

hearing." (35)

How to explain

this sudden passion of the supposedly macho Arabs for Al Jazeera's

powerful women. While Amin Hussein, a mass communication expert,

gives a technological answer to the question (the satellites'

empowerment of women), the artist Hisham Ghanem offers a more

sophisticated psychoanalytical explanation-the Arab male's

identification with the woman as the victim who is taking revenge on

her aggressors. For Amin Hussein, "Arab satellite services have

responded to the demand of Arab women to portray their true image

and role in society to balance the common stereotype in the West of

the downtrodden Arab woman without rights and without a role to play

other than daughter, wife and mother." According to his analysis,

"Talk shows, news, and programs feature interviews with female

leaders in business, government, politics, and diplomacy ... rather

than covering only their role in the household of food preparation

and as sex symbols in television commercials and video-clips." (36)

But for Ahmed Ghanem, an artist who is more interested in esthetics

and hidden emotions, technology does not explain it all.

Ahmed

Ghanem was one among the dozen intellectuals whom the Kuwaiti

magazine Al Funun ("The Arts") invited to contribute to their

summer 2002 issue on decoding the mystery of the Fada'iyyat. Unlike

our much more publicized extremists, Ghanem feels empowered by a

woman's strength. As both an artist and a designer, he goes into

detail in his study on "The Esthetics of the Private Satellite

Channels." He argues: "If we consider the laws and psychological

mechanisms which in each satellite channel define for the female

speaker the code for dressing and expressing oneself, as well as the

way she uses the screen's space to unfold her personality, then we

cannot escape noticing that the aggressive (hujumi) style of the Al

Jazeera female speakers is a very distinctive kind of beauty which

is very specific to them and makes them stand out when compared to

other channels, especially if we remember that Al Jazeera is a news

(as opposed to entertainment) channel, and that these women's job is

to inform the viewer. The fact that the majority of this channel's

female speakers are far from being young and insecure and display on

the contrary maturity in both age and emotional equilibrium gives

them a cerebral charisma and audacity which exercises a particular

enchantment on the viewer. The Al Jazeera female speakers exude a

spell-binding fascination which transcends physical attraction."

(37)

Could it be

that Al Jazeera's powerful women have such an attraction for Arab

men because they trigger childhood fantasies when they enjoyed their

mothers' story-telling and improvisations on the "1001 Nights"?

Could it be that the satellite is reviving Arab men's childhood

universe where Scheherazade, the powerful female inventor of

adventures, empowered them as children? What is certain, according

to Ghanem, is that by contrast to Al Jazeera where women's strength

reflects the freedom of speech they enjoy as journalists on that

channel, the superficial beauty of the fragile female speakers in

entertainment channels reflects a passivity which does not excite

him as a man, if only because, as he says, passivity "mirrors the

rules of the game on those televisions. Rules which reveal that only

the masters are players." (38) What is extraordinary about Ahmed

Ghanem's analysis of digital Islam's new game, is that, as a male,

he does not identify with the masters, the princes or ayatollahs who

can afford to buy satellites, but on the contrary, he feels his own

fate to be linked to that of the women. In my view, it is this

rejection of the archaic role of the dominant male, whose

masculinity increases with women's passivity, which is the news in

digital Islam.

Conclusion

The novelty in

this digital Islam galaxy is that many Arab men craving their own

emancipation from authoritarian censorship have become alert enough

to disconnect power from sex. Many of the male viewers of satellite

broadcasting do not seem to think that their masculinity is

threatened if women show their power. The problem now is how to

interpret this new phenomenon.

Is this only a

transient phase or are we witnessing a civilizational shift in the

perception of the difference? Are the satellite-connected Muslims

growing to perceive the sexual difference as enriching? Are they

even preparing themselves to embark on a less threatening global

universality? Is the satellite reviving the cosmic vision of the

Sufis, the mystics of Islam who perceive the difference as

enriching?

For the Sufi,

the stranger (the different other), be it the woman or the

foreigner, is not a threatening enemy. On the contrary, Sufis

celebrate diversity as an enchanting display of human complexity in

their concept of the cosmic mirror. "The mirror is like a single

eye, while the forms (it reveals) are various in the eye of the

observer" is how Ibn 'Arabi, born in Murcia (Spain) in 560 of the

Hijra (1165 of the Christian calendar), encouraged his

contemporaries to enjoy foreigners as fabulous reflections of the

same divine being. "The essence of primordial substance is single,

but it is multiple in respect to the outer forms it bears with its

essence." (39) It is not only femininity alone which emerged in

satellite broadcasting as a challenge, it is also the question of

minorities, be they religious, or ethnic, such as the Kurds and the

Berbers, which are claimed as positive enrichment. Morocco has

declared Berber to be a national language and established an

institute to enhance it as a vital dimension of a dynamic society.

(40) The satellite has changed the frame in which the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict is addressed in such a way that

exclusion of either party is ruled out: "Palestine-Israel: Peace or

a Racist System?" (41) This how the influential Palestinian

journalist Marwan Bishara frames the question, ruling out any

extremist alternative which is a negation of peace. It is no more

"does the state of Israel have the right to exist or not" which is

at stake, but how can harmony be engineered from the difference that

is the challenge everyone is facing.

As for the

Sufis and women, it is no wonder that male Sufis celebrate

femininity as energy, an opportunity for men to blossom and thrive.

For Ibn 'Arabi, the female lover is "tayyar" or, literally, endowed

with wings, an idea that the Muslim miniature painters often tried

to capture. Sufi men seem to explore the subconscious of the Muslim

psyche where myths and legends, sacred and profane, endow women with

extraordinary powers. From the dazzling Queen of Sheba to the

irresistible Zuleikha in the sacred Koran, to horse-riding Shirin in

the Persian legends and the subversive Scheherazade in Arabic tales,

to modern women artists today, the feminine stands as a challenge in

Islamic art. This brings us to understand better why intellectually

dazzling female Al Jazeera hosts enchant male viewers.

But there is

one final emotional nuance I would like to add which seems to me

pertinent if we are to grasp the nascent trends of the digital Islam

galaxy: Sufis were very popular in a medieval Islam which had to

face the constant attacks of Christian crusaders because they

addressed the question of fear. Sufis helped people in medieval

Islam to face fear of the unknown by diving into knowledge." The

human being can master his anxieties by channeling his energies into

learning ... The issue is confusion. Confusion creates anxiety

(hayra), and anxiety creates movement and movement is life." (42)

Fear is OK,

says the Sufis, because it triggers in you the desire to know what

frightens you. In so doing, it produces a positive movement within.

The worst is to be petrified by one's fears to the point of being

paralyzed and forced to shrink inward. And anxiety is indeed the

daily share of many of us, Muslims or not, who witness the

apocalyptic vanishing of our familiar frontiers. TBS.

This

abridged version of THE SATELLITE, THE PRINCE AND SCHEHERAZADE: The

Rise of Women in Digital Islam by Fatema Mernissi, Copyright (C)

2003 by Fatema Mernissi, is reprinted by permission of the Edite

Kroll Literary Agency Inc. All rights reserved.

Endnotes

1.

Mohammad Mahmud "Darura am ighra? Dirama Ramadan" ("Necessity or

Seduction? Ramadan Films") in the TV Programs insert of Al-Ahram

Al-'Arabi, Issue 299, December 2002, p. 18. Al-Ahram Al-'Arabi

is a Cairo-based avant-garde magazine. Website:

www.ahram.org.eg/arabi.

2. Zaynab

Muntashir "Qasim Amin wa-Faris Bila Jawad:

bayna harim as-sultan

wal-sultan nafsih" ("Qasim Amin and Rider Without a Horse: Between

the Sultan's Harem and the Sultan Himself") in the Television column

of the magazine Rose El Youssef, Issue 3885, November 23-29,

2002.

3. Husam 'Abd

al-Hadi "The Empire of Women: of 80,000 Employed in Radio and

Television, 50,000 are Women," a survey published in the Ramadan

issue of the Egyptian magazine Rose El Youssef, Issue 3886,

November 30-December 6, 2002, pp. 43-45.

4.Tariq Ali in

his Suhun Fada'iyya ("Satellite Dishes") column in Al-Nuqqad,

June 17, 2002. Al-Nuqqad is a Pan-Arab political and cultural weekly

magazine with offices in London and Lebanon. Website:

www.annouqad.com

5. Jamal

al-Kashki "The Halal-Haram Fatwas" (Fatawi al-Halal wal-Haram) in

the special Ramadan Issue of Al-Ahram Al-Arabi, Issue 295,

November 16, 2002, p. 73.

6. "Aftahu

fi-l amri, abana lahu .... and the verse of the Quran yastaftunaka

qul Allahu yuftikum [Sura 4 Al-Nisa' ("Women"), Verse 176] ay

yas'alunaka su'ala ta'allumin ...." Ibn Manzur Lisan

al-'Arab, Dar al Maarif, Cairo 1979 edition, volume 5, page

3348. Ibn Manzur was born in Cairo in 1232 and died in

1311.

7. Jadal, the art of interactive debate central to the

spread of Islam as an oral communication strategy (before the

introduction of paper by the Persian Wazir Ja'far al-Barmaki

strengthened the despotic bureaucracy of the Abbasid dynasty). It

was the object of a whole school of dialogue training manuals such

as the 13th-century Ibn 'Uqayl's The Book of Jadal According to

the Way of the Theologians (Kitab al-jadal 'ala tariqat

al-fuqaha). Maktabat al-Thaqafa al-Diniyya, Port Said, Egypt, n.d.

The author died in 510 A.H. (13th century). Today, we witness a

renaissance of jadal, and books teaching dialogues are becoming

best-sellers again. Such is the case with my Moroccan contemporary

Taha Abderrahman's book On the Tradition of Dialogue (Fi usul

al-hiwar), Al Markaz al-Thaqafi al-'Arabi, Casablanca, second

edition, 2002), which has been reprinted in response to the great

demand..

8. Jamal

al-Kashki, idem.

9. Peter Mandaville "Digital Islam: Changing

the Boundaries of Religious Knowledge" in the International

Institute of the Study of Islam in the Modern World Newsletter,

March 1999, pp. 1 and 23. This newsletter is a tri-annual

publication of Leiden University, Netherlands.

Website:http://isim.leidenuniv.nl

10.

"maqsiduhum maqsidun wahid" Lisan al-'Arab, Volume 1, p.

134.

11. Peter

Mandaville "Digital Islam" op.cit. To get a quick glimpse of the

speedy digital Arab galaxy build-up, the following two books are

quite useful: René Naba: Guerre des Ondes…Guerre des Religions: La

Bataille Hertzienne dans le Ciel Méditerrannéan, L'Harmatan, Paris

1998 and Mohamed El-Nawawy and Adel Iskandar Al Jazeera: How the

Free Arab News Network Scooped the World and Changed The Middle

East. Westview, Perseus Books Group, Massachusetts,

2002.

12. Naomi Sakr

"Arab Satellite Channels Between State and Private Ownership:

Current and Future Implications" in Transnational Broadcasting

Studies Issue 9 (TBS 9), Winter-Fall 2002, p 3. Website:

www.tbsjournal.com.

13. Naomi

Sakr, op.cit.

14. Hussein

Amin "Arab Women and Satellite Broadcasting" in Transnational

Broadcasting Studies Issue 6 (TBS 6), Spring/Summer 2001.

Website: www.tbsjournal.com. Amin Hussein is chairman of the

Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at the American

University in Cairo and has produced impressive work on the topic of

new technologies.

15. Driss

Bennani: "L'Iran Drague Nos Journalistes" in the Moroccan

weekly

Tel Quel, Issue 46, October 5-11, 2002.

16. "Who

Controls LBC?" According to Mohamed El-Nawawy and Adel Iskandar, LBC

will be controlled by a board nominated by ministers and officials

close to the Syrian government and not by Rafik Al Hariri, as many

think. According to them, Rafik Al Hariri partially owns another

Lebanese TV channel, Future TV (op. cit.).

17. Assya Y.

Ahmed "The Closing of Murr TV: Challenge or Corrective for Satellite

Broadcasting in Lebanon" in Transnational Broadcasting Studies

9 (TBS 9), Winter-Fall 2002. Website:

www.tbsjournal.com.

18. Mohammed El-Nawawy and Adel Iskandar,

op.cit., p. 39.

19. "Akbar

safaqa Sa'udiyya-Lubnaniyya li-damj at-tilifizyun bis-suhuf"

("The Biggest Deal between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon to Merge

Audiovisual with Printed Media") in Al-Nuqqad, March 2002, p.

16 (cover story).

20. Duncan

Campbell "US Plans TV Station to Rival Al Jazeera" in The Guardian,

Friday November 23, 2001.

21. David

Chambers "Will Hollywood Go to War?" in Transnational

Broadcasting Studies 8 (TBS 8), Spring-Summer 2002. Website:

www.tbsjournal.com

22. Abdallah

Schleifer "Super News Center Setting Up in London for Al-Hayat and

LBC: An Interview with Jihad Khazen and Salah Nemett" in

Transnational Broadcasting Studies 9 (TBS 9), Winter-Fall

2002. Website: www.tbsjournal.com.

23.

Al-Nuqqad, op.cit.

24. The source

for the statistics on illiteracy rates is the UNESCO Statistical

Yearbook for 1999, Table II.5.1.: "Estimated number of adult

illiterates and distribution by gender and by region.1980, 1999 and

2000."

25. Naomi Sakr

"Arab Satellite Channels between State and Private Ownership"

op.cit.

26. Chris

Forrester "Middle East TV Continues to Baffle and Bewilder" in

Transnational Broadcasting Studies 9 (TBS 9), Fall-Winter

2002. Website: www.tbsjournal.com. Chris Forrester is a broadcast

journalist and the author of Digital Television Broadcasting

published in June 1998 by Philips Business

Information.

27. Nabil Ali "Thuna'iyyat al-asr: al-sifr

wal-wahid" ("The Century's Duality: the Zero and the One") in

Wijhaat Nazar ("Points of View, an Egyptian monthly review),

Volume 4, Number 44, September 2002, pp. 34-40. Website:

www.wighaatnazar.com.

28. Tourya

Guaaybess "A New Order of Information in The Arab Broadcasting

System" inTransnational Broadcasting Studies 9 (TBS 9),

Fall-Winter 2002. Website: www.tbsjournal.com.

29. Abdallah

Schleifer "An Interview with Ali Al-Hedeithy, the Director General

of MBC" inTransnational Broadcasting Studies 9 (TBS 9),

Fall-Winter 2002. Website: www.tbsjournal.com.

30."12, 5% de

son programme à des émissions religieuses, contre 75, 5 pour les

variétés et 9, 5 pour cent pour l'information …." René Naba op. cit.

p. 85.

31.Walid Najm

"Cultural Programs: The frequency is ridiculously low and the

content is totally divorced from reality" in Al-Funun (a

Kuwaiti magazine), Issue 6, June 2001. p.39. The issue is devoted to

a survey of Arab satellite channels.

32. Abdallah

Schleifer "Interview with Ian Ritchie, Former CEO of MBC" in

Transnational Broadcasting Studies 7 (TBS 7), Fall-Winter

2001. Website: www.tbsjournal.com.

33. Mohamed

El-Nawawy and Adel Iskandar op cit., p. 59

34. Naomi

Sakr, op.cit.

35. Tariq Ali,

op.cit..

36. Hussein

Amin, op. cit.

37. Ahmed

Ghanem Shakl al Fada'iyyat al Khassa Yataqqadam ("The

Aesthetics of Private Satellite Channels Are Improving") in

Al-Funun 6, June 2001, p. 38. Website:

www.kuwaitculture.org

38. Ahmed

Ghanem, op. cit.

39. Ibn 'Arabi

Fusus al-Hikam ("The Bezels of Wisdom"). The English

translation used here is that of R. W. Austin: "The Bezels of

Wisdom," Paulist Press, New Jersey, USA, 1980. The quote is on page

233. The original text of the first quote reads fal-mir'atu

'aynun wahidatun, was-suwaru kathiratun fi 'ayn al-ra'i. Dar

al-Kitab al-'Arabi, Beirut, Lebanon, date not indicated, p. 184.

40. Since

Berber was declared a national language, you notice regularly in the

news stands magazines with its unfamiliar alphabet challenging you

to learn its mysterious code, such as Le Monde Amazight and Tasafut

("Candlelight").

41. Marwan

Bishara Falastin-Isra'il: salam am nizam 'unsuri?

("Palestine-Israel: Peace or Racist Regime?"). Cairo, Markaz

al-Qahira li-Dirasat Huquq al-Insan, 2001.

42. My

translation of the following quote: Fal-Huda huwa an yahtadi al

insan ila l-hayrati fa ya'lam. Inna l-amra hayratun wal-hayratu

qalaq wa harakah, wal-harakatu hayat. Fala sukuna fala mawt, wa

wujud, fala 'adam in Fusus al-Hikam (p. 200). TBS |