Syria’s Curious Dilemma

Bassam Haddad

(Bassam Haddad teaches political science at St. Joseph’s

University in Philadelphia.)

|

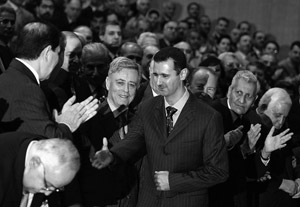

Syrian President Bashar al-Asad stands with then

Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass (right) and Hasan al-Turkmani,

chief of staff, as they visit the tomb of the unknown soldier

in Damascus, October 6, 2002.

(Reuters/SANA/Landov) |

Seasoned observers of Syria have learned not to make much of

apparent political changes in the country. This lesson holds true

today, but with a twist.

Five

years after the death of Hafiz al-Asad, who ruled Syria for 30

years, a series of “springs” have come and gone without

substantially opening up the political system. The country’s

political institutions are stable, but stagnant, including the

governing Baath Party, which continues to rule by periodically

reshuffling elites. Syria’s economy continues to sputter, its small

oil reserves continue to dwindle and its work force continues tolag

in acquiring the skills needed in today’s global economy. Perhaps

the most troubling part of Syria’s predicament is an invisible but

rising wave of poverty unprecedented in recent history.

For

Syria’s political elite, this precarious state of affairs is not

unusual. Nor is it beyond the wherewithal of the awkward, yet

maturing new leadership around President Bashar al-Asad to deal with

adversity. What has changed rather decisively is the world around

Syria’s cocoon. Coupled with domestic woes, this change does

challenge the abilities of the regime. Violent regime change in

Iraq, the humiliating loss of Syrian control in Lebanon and a

strident Israel emboldened by a duplicitous “war on terror” have

combined to isolate Syria and to diminish its regional influence.

The results of negotiations with the European Union to bring Syria

into a “partnership agreement,” as part of the EU’s “Barcelona

process” of Euro-Mediterranean economic integration, have been

disappointing. To make things worse, the Bush administration, backed

by Congress, persists in pursuing an unprincipled anti-Syria

campaign whose endgame remains difficult to divine.

In

2005, Syria finds itself bereft of foreign policy tools whose

advantages it enjoyed for over 30 years. Between 1970 and 1990, the

Syrian regime benefited from the superpower competition of the Cold

War. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990, Damascus

relied on playing a regional role, beginning with its participation

in the US-led coalition to expel the Iraqi army from Kuwait in 1990.

Now, the international and regional fronts are both closed, and the

Syrian regime is left with a lone front on which to fight for its

viability: at home. The domestic front is where the regime has

historically been most vulnerable.

Barring unforeseen developments, the Syrian regime faces

what, by its lights, is a curious dilemma: either it acquiesces to

the demands of external forces in order to preserve itself or it

compromises its domestic position by allowing the diffusion and

decentralization of power. Does the Syrian regime have the skill and

the willpower to escape from this hornet’s nest? Can the regime

manage today’s domestic, regional and international crises all at

the same time? Judging by the outcome of the Baath Party’s recent

Tenth Regional Conference, one should not hold one’s

breath.

Back to Basics

|

Aleppo from above. (Issa

Touma) |

The

Tenth Regional Conference, held in early June 2005, was a bit of

housekeeping in preparation for an entrenchment. It saw the apparent

consolidation of Bashar al-Asad’s rule at a time when significant

external and internal tensions and threats are coinciding for the

first time since the 1960s. According to Ibrahim Hamidi, perhaps the

most informed and incisive journalist in Syria today, “The message

that the Regional Baath Conference wanted to send at the end of the

conference to public opinion, the opposition and foreign

actors—especially America—is that the Baath Party will remain the

ruling party in Syria.”[1]

Very

little was said at the conference about foreign policy, beyond

affirmation that peace will remain Syria’s “strategic choice” and

that the regime will work to enhance its bargaining position

vis-à-vis Israel. Indicating the regime’s domestic focus, Bashar

emphasized that “any decisions or recommendations made during the

conference should express our internal needs only, in isolation from

any other considerations aimed at pushing us in directions that

contradict our national interest or threaten our stability.”[2]

The

conference was not without positive developments, though these were

hardly far-reaching reforms. Expanding space for political

participation was a recurring theme. For the first time, there were

serious recommendations that the state should review the Emergency

Law in place since 1963, with an eye toward “narrowing the scope of

state security matters.”[3] A new “political parties law” is likely to

take effect soon,[4] though Article 8 of the constitution,

designating the Baath Party as the “leader of state and society,”

will remain untouched. Reiterating a stock line, a high-level

official told the pan-Arab daily al-Hayat that modification

of Article 8 is an “external request” made by non-Syrian interests.

This statement is related to various proclamations during the

conference regarding the need to “lay bare” the intentions of the

expatriate opposition, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood

leadership in exile in Paris, on the grounds that they are not true

“nationalists” and are being supported by actors hostile to Syria.[5] Another likely subject of this denunciation is

the Reform Party of Syria led by Washington-area dentist Farid

Ghadry, a would-be Syrian Ahmad Chalabi who is being promoted by the

neo-conservative think tank, the Foundation for the Defense of

Democracies.

In

various interactions, formal and otherwise, Bashar emphasized that

“the party does not own the state.”[6] It is necessary, he said, “to redefine the

relationship of the party to political power, and not to be enmeshed

in daily politics, and to move away from office work and focus on

interacting with the masses.”[7] Henceforth, the Baath’s share of cabinet posts

will be limited to ten.[8] Nonetheless, it was stipulated toward the end

of the conference that the prime minister and the speaker of

parliament must be members of the Baath’s ruling body, the Regional

Command, creating an obvious contradiction between proclamations and

practice, and eliminating the possibility that a high-level

executive such as the prime minister may be an

independent.

It

was also suggested that the Regional Command of the party be

dissolved and replaced by the “Party Command.” Hence, President

al-Asad would become the secretary-general of the Baath Party, not

the regional secretary. This move would facilitate the dissolution

of the National Command of the party in the near future.[9] Although the party did not act on this

suggestion at the conference, it is likely to do so in the future.

In any event, the number of members in the Regional Command was

dropped from 21 to 14. It is also significant that there were forces

calling for replacing the slogan “unity, freedom, socialism” with

“democracy and social justice,” and the name Arab Socialist Baath

Party with simply the Baath Party, thereby toning down the socialist

identity of the party and introducing the magic word “democracy.”[10] These changes did not occur, but talk of

them provides clues to the regime’s longer-term thinking.

The Nitty Gritty

|

Bashar al-Asad shakes hands with party members during

the opening of the Baath Party Regional Congress in Damascus,

June 6, 2005. ‘Abd al-Halim Khaddam, then still vice

president, is seen smiling next to Asad. (Ramzi

Haidar/AFP) |

It

is no secret that Syria’s real strongmen sit at the helms of General

Security, Military Security and the Republican Guard. Changes and

replacements at that level tell a more direct story about the

regime’s internal power dynamics than hundreds of pages of party

declarations and memoranda. One week after the conference, Bashar’s

brother-in-law Asef Shawkat was confirmed as the head of military

intelligence, perhaps one of the most sensitive and powerful

positions in Syria today. Manaf Tlass, son of former Defense

Minister Mustafa Tlass, and Bashar’s brother Mahir are the effective

heads of the Republican Guard, perhaps the most potent fighting

force in Syria. The implications here might appear clearer than they

are, for family ties to Bashar do not guarantee loyalty, as the

history of struggle for power in Syria instructs.

More

important is the evident “clearing of the way” that has taken place

within the predominant institutions of coercion in the country since

Hafiz al-Asad’s death. Over the past five years, strongmen who are

either opposed to Bashar or are not part of his “team” have been

gradually either replaced or “retired.” They include former Chief of

Staff ‘Ali Aslan and his deputies ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sayyad, Faruq

Ibrahim ‘Isa, Ibrahim al-Safi, Shafiq Fayyad and Ahmad ‘Abd al-Nabi,

the head of the political security branch of General Security,

‘Adnan Badr Hasan, and Hasan al-Khalil, Shawkat’s predecessor as

head of military intelligence.

Perhaps the most visible development at the Regional Baath

Conference was the replacement within the Regional Command of what

remains of the “ old guard” that surrounded Bashar’s father[11] with a “new” team.[12] A charter member of the old guard, ‘Abd

al-Halim Khaddam, “resigned” as vice president and as a member of

the Regional and National Command Councils after sensing the

isolation of the “older” Baathists. As Khaddam is perhaps the second

most visible icon of the Baath regime after Hafiz al-Asad, the

nature of his exit—which was not “honorable”—bespeaks the end of an

era. The circumstances surrounding his exit lend credence to the

little-discussed story that Khaddam and others among the old guard

formed an informal alliance aimed at “saving” the regime from what

they perceive to be the current leadership’s blunders in Iraq and

Lebanon.[13]

Khaddam’s departure completes the process of paving the way

for Bashar that started in June 2000. The new team is made up of

both older and younger Baathists who are distinguished by their

proximity to the current leadership, and not necessarily by their

skill or experience. It is said that this team is important not for

what it will do for Syria, but for what it will not do: obstruct

decisions made by the top leadership. For the regime, the new team

is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, its unquestioning loyalty

will make for a less erratic policy. On the other hand, the new

Command leadership lacks vision and, many say, competence. It

remains to be seen which edge of the sword will strike. If the new

team is a short-term fix to rid the leadership of troublemakers,

then it could enable a smoother and surer decision-making process in

the future. However, if the desired end is to surround the

leadership with complacent figures in perpetuity, then it is

probable that Syria will return to square one, with the leadership

approaching a stifling absolutism of sorts. In any event, Syria’s

principal dilemma leaves little room for the long-term

sustainability of such a formula.

Institutionally speaking, Bashar and his closest allies have

played a delicate game to consolidate their control. On the one

hand, they needed to preserve the structure of executive authority

by strengthening the party and government institutions; on the other

hand, they had to manipulate the same authority structure and

institutions that would allow them to limit the personal power of

potential adversaries in the long run. This was not a choice of one

strategy among many on offer: Bashar needed, and needs, the Baath

Party. Since he lacks his father’s charisma, and with the

multiplication of power centers around certain personalities within

the regime, selective reinvigoration of the roles of the party was

the only rational choice.

Another change is increasing reliance on the security

services, as indicated by the shifting membership in the Regional

Command. Historically, the Command included the chief of staff and

the defense minister. After the June conference, two members of the

security services took the spots of these officials in the Command.

It is unmistakable that the security services are continuing to gain

authority in circles that they began to infiltrate in the early

1970s. Finally, the institutional army's clout has been eroded,

particularly after the pullout from Lebanon.

The Balance Sheet

|

Fraying poster of Hafiz al-Asad in Damascus, 2004.

(Thomas Kern/Lookatonline) |

The

transition of regime from Asad senior to Asad junior that began in

2000 (and perhaps earlier) is now complete. Though the new regime is

not impregnable, the intra-party tension and the rocky

decision-making processes that characterized Bashar’s first five

years in power are unlikely to reappear for some time. The evident

winners are Bashar and his team, including the Asad family and their

innermost circle. The evident losers are the old guard, or those who

opposed Bashar’s ascendancy, beginning with formerly powerful Chief

of Staff Hikmat Shihabi, who “retired” in 1998 after he made public

his distaste for the prospect of Bashar ruling Syria, and ending

with Khaddam—with a flurry of others in between.

Digging a little deeper, one finds that the decisive break

was made not only with the old guard, but with the regime of Hafiz

al-Asad, a development that cannot be translated publicly into words

in Syria’s political climate today. Bashar was indeed his father’s

choice of successor, following the death of his oldest son Basil in

a 1994 car crash, but it is questionable whether Asad senior wanted

Bashar to change the regime itself. This is not an academic point,

for with the changes to the regime came changes in the regime’s

style and approach whose contours are still emerging.

In

its handling of the US invasion of Iraq and the aftermath, the

“Lebanon file” after the May 2000 Israeli withdrawal and the US “war

on terror” that linked Syria with “terrorist” groups within Syria

and in Lebanon, the current Syrian regime has contributed to its own

isolation. This isolation is exacerbated by the Bush

administration’s hostile posture. Hafiz al-Asad’s regime boxed

itself in domestically, but was always able to compensate for

problems caused by its centralization of domestic political power by

adopting an uncompromising stance on regional issues—particularly

the Arab-Israeli conflict. Bashar’s regime has been steadily losing

this ability. In the past, Palestinian and Lebanese resistance

movements were used from a distance to prop up the legitimacy of the

Syrian regime. Today, the regime has absorbed these tools as part

and parcel of its legitimacy, thereby compromising its independence

and allowing itself to be more liable for the Palestinians and

Lebanese groups’ possible missteps. In the post-September 11

international climate, where the US, Europe and Israel require no

hard evidence to condemn Syria for any number of alleged

infractions, such a loss of autonomy could subject Syria to many

unneeded blows. One should caution against accepting the common view

in Syria that Asad senior would never have brought the country to

such a point. The Syrian regime has been, and still is, willing to

pay nearly any price to maintain its own security, and the dead end

was always in sight. Asad senior was likely, however, to have

delayed the inevitable a little longer.

The

breathing space that the regime afforded itself by clearing the way

for a less conflict-ridden decision-making process is an opportunity

to embark on irreversible domestic decentralization that would

herald an era of putting development ahead of both regime security

and external demands. Independent, opposition and regime-friendly

observers in Syria will not bet on this scenario. In view of the

Bush administration’s aggressive policy orientation, the smart money

is on a strategy of gradual submission to external demands that may

hurt the wellbeing of the Syrian people, but will keep the regime's

security intact. The same scenario is likely to unfold in the case

of the country’s political economy.

State of the Economy

The

state of the Syrian economy remains dismal. It is unclear whether

the deliberations at the recent Baath Regional Command Conference

reflect the sophistication that is required to deal with the

crisis.[14] Optimists continue to debate whether this or

that liberalization measure is likely to improve the economy as

though the missing link is a “good plan.” The announcement by the

chief of the State Planning Commission in 2004 that Syria will adopt

the principles of a market economy by 2010 brought relief to

optimists.[15] So did the announcement at the Baath

Regional Conference that Syria will adopt a “social market

economy.”[16] But what about the elephants in the room?

Syria’s economy stagnated between 1996 and 2004, with an

estimated average growth rate of 2.4 percent.[17] Meanwhile, the population is growing at a

rate of 2.7 percent,[18] spelling disaster for development. Economic

growth reached 3.4 percent in 2003, but that unusually high rate

reflected the sale of Iraqi oil through Syria and then the rise of

oil prices as a result of the Iraq war. In 2004, economic growth

dropped to 1.7 percent, showing the danger of depending on oil

rents.[19] Oil production reached 591,000 barrels per

day (bpd) in 1995 but declined to 450,000 bpd in 2005. According to

one estimate, Syria will become a net importer of oil for the first

time in 30 years by 2012.[20] The good news for the Syrian regime is that

the rise in natural gas production is likely to compensate for a

substantial part of the decrease in oil production. Gas reserves are

estimated at 240 billion cubic meters.[21] Much depends on the transit revenues that

Syria will receive from the Arab Gas Pipeline linking Egypt with

Turkey and eastern Europe.[22] Ultimately, rent income from oil or gas will

only buy time. Meanwhile, unemployment, poverty, investment and

dilapidated public-sector firms require immediate attention.

Syrians are suffering from an alarming decrease in their

standard of living. In 2003-2004, 5.1 million people (or 30.1

percent of the population) were living below the poverty line, with

2 million Syrians unable to meet their basic needs.[23] By most estimates, there is 20 percent

unemployment in the country, with at least 300,000 new workers

entering the job market each year.[24] According to former State Planning

Commission chief and current Deputy Prime Minister for Economic

Affairs ‘Abdallah al-Dardari, an average annual growth rate of 7

percent will be necessary to provide employment for job seekers.

Where will this growth come from?

With

oil income tapering off, Syria’s public and private sectors must do

the heavy lifting. To generate growth in those sectors, the regime

appears to be counting on the trade benefits of a partnership

agreement with the EU. After some hesitation, and presumably to

break the Syrian isolation imposed by the US, in 2004 Bashar created

a new team to speed up the signing of an agreement. As a

precondition, the EU pressed for a rapid transition from a public-

to a private-sector economy, and, according to former Industry

Minister ‘Isam al-Za‘im, the regime soon found itself moving faster

and conceding more than it wanted to. By the end of 2004, the EU had

added new preconditions, including a call upon Syria to lead the way

in eliminating weapons of mass destruction from the region.

Nevertheless, the Syrian team included “services” in the list of

sectors to be liberalized, and at a faster pace, as a way to hasten

the signing. This concession was not made public. In the end, after

the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri,

the EU withdrew its promises of an expedited agreement.

Should the negotiations restart, the public sector would have

to be overhauled, a political nightmare for a regime such as

Syria’s, where that sector takes on a number of necessary political

and social functions. Privatization according to a plan of

eliminating failing public-sector firms and refurbishing struggling

ones might work only if the top leadership is willing to compromise

the non-economic functions that the sector serves. More importantly,

the plan would fall to pieces in the absence of a private sector

capable of employing at least half of the new job seekers each year

(150,000-200,000 people), a figure that is well beyond the capacity

of Syria’s mostly small private firms.[25]

The

growth of the private sector in Syria was erratic in the 1990s.[26] Since 2000, private investment grew slightly

only because of the dramatic drop in such investment between 1996

and 2000. The most recent figures place the private sector’s

contribution to capital accumulation at only 34 percent, after years

of supposed support and promotion of private sector growth.[27] Obstacles to private-sector growth remain

both political and structural, having to do with the political role

that the public sector plays in servicing the regime’s economic

power and social legitimacy. Another part of the problem has been

the failure of existing public and new private banks in financing

the growth of the private sector.[28] As a result, new entrants into the private

sector remain few. By contrast, the already existing private

businessmen and the public-private networks to which they belong are

expanding at a steady pace as they are faced with little or no

competition from potential entrants who lack financing. These big

business groups worry not about liberalization or lack thereof at

this point; they are mostly concerned to keep the formula within

which they are accustomed to work. One might have to wait for a

vigorous economy until these individuals and networks discover a

contradiction between further capital accumulation and the existing

formula. For the time being, the idea that a partnership agreement

with the EU can provide the cure for Syria’s economic ills is

incommensurate with the political and institutional requirements of

such an agreement.

Moment of Decision

According to Nabil Sukkar, a seasoned economist and business

consultant, “There is a need for a ‘Great Leap Forward,’ not an

incremental progression.”[29] Syria’s economy remains captive to the

country’s brand of centralized politics. Economic rationality

remains severely fettered by a political logic that prevents the

very idea of a comprehensive reform plan, without which incremental

measures are ineffective at worst and reversible at best. Problems

of low investment, an inhospitable environment, a weak judiciary and

idiosyncratic state intervention are not economic, but political

through and through. According to Za‘im, these problems have existed

since 1991 when Syria embarked on “economic pluralism.” Beyond the

lack of political will needed to overhaul the Syrian economy, there

are three equally large obstacles: the network of state officials,

military officers, their offspring and relatives, and powerful

businessmen who benefit from the current arrangements; a decrepit

administrative and bureaucratic system; and an insufficiently

skilled labor force. Only 10 percent of Syrian workers have a

college degree, for instance.[30] It is impossible to treat these problems in

isolation, requiring once again the kind of political will that

would put Syria’s development before regime security.

The

official line is that Syria is prevented from taking certain reform

measures because they correspond to external demands. This is a

false binary opposition. It is true that Syria is facing a hostile

international environment and an unprincipled political campaign

against it, but that has been the case since the early twentieth

century. The hostility is unlikely to subside, whatever the stance

of the United States. Proper development for state and society in

Syria does not conflict with warding off external enemies. On the

contrary, it is the most efficient weapon against them.

For

better or for worse, and unless Baathist infighting resurfaces, the

Syrian regime is left to its own devices on the domestic front as it

attempts to resolve its curious dilemma. Proper development does

conflict with the guaranteed security of the Syrian regime as it

stands today. The Syrian regime is quickly approaching the point

where it will have to choose between compromising with the outside

forces it cautions against, thereby preserving itself in its current

form, or compromising with the Syrian people, thereby voluntarily

reducing its own power. Much anti-Zionist and anti-imperialist

rhetoric notwithstanding, this choice is not in the end such a big

puzzle.